Upper left: Hermissenda crassicornis; Upper right: Okenia rosacea;

Lower left: Peltodoris nobilis; Lower right: Melibe leonina;

Four nudibranch species exhibited at the Monterey Bay Aquarium

In the previous post, I have gone to great lengths to show why most nudibranchs are simply not meant to be kept in aquariums, mostly due to their highly specialised diets. However, there is a small minority of nudibranch species that can survive in an aquarium, provided their food requirements are met.

NUDIBRANCHS IN PUBLIC AQUARIUMS

A quick search reveals that few if any public aquariums have nudibranchs on display. Perhaps the most notable exception to this rule is the world-famous Monterey Bay Aquarium. It has four species on display, three of them in its Rocky Shore exhibit:

Hermissenda crassicornis, which is an exception among nudibranchs, in that it is quite a generalist where it comes to feeding. More on that later. (Photo by * Alicia)

Okenia rosacea, which is a predator on a particular species of pink bryozoan. (Photo by jalbersmead)

Peltodoris nobilis, a specialist on sponges. This species is actually said to give off a citrus scent when disturbed, and is affectionately known as the 'sea lemon'. (Photo by Bill Bouton)

Note that these are all species that can be found in the waters of Monterey Bay. Presumably, apart from the generalist Hermissenda crassicornis, the aquarium either manages to culture the necessary prey species in captivity, or has a steady supply of prey from the wild to feed their captive nudibranchs.

NUDIBRANCHS AROUND THE WORLD

Many people might be under the impression that nudibranchs are an exclusively tropical group, but the fact is, nudibranchs are a truly global group. They can actually be found in all the world's oceans, living within a wide array of habitats and ecosystems, encompassing lifestyles such as pelagic drifters in the open ocean, and colourful benthic dwellers in the tropical coral reefs of the Indo-Pacific and kelp forests of North America's Pacific coast; from the seas surrounding the British Isles to New Zealand, and even in frigid Antarctic waters!

Instead of having to buy nudibranchs collected from halfway around the world, aquarists might do better to look at the nudibranch diversity closer to home, as it would definitely be much easier to find and obtain the right prey for local species.

Which brings me to another point, that of proximity to the shores. Aquarists interested in trying to keep nudibranchs in aquaria, and with ready access to the shore, can always experiment with those found locally. Not only is it possible to directly observe the behaviour of nudibranchs in the wild and find out their diet, it is possible to collect nudibranchs along with their prey. If attempts to culture the necessary prey species in captivity fail, the aquarist still has the option of collecting more of the prey species from the shore. Of course, all this should be done only when local environmental conditions are able to sustain a limited level of collection.

Hermissenda crassicornis: THE BEST CANDIDATE FOR THE AQUARIUM?

I mentioned earlier on that the opalescent nudibranch (Hermissenda crassicornis) is quite a generalist where it comes to diet, which lends it particularly well to being raised in captivity.

Its primary prey in the wild appears to be various species of hydroids, although observation in the wild have recorded it preying on other nudibranchs and possibly small bivalves, and experiments in marine laboratories have shown that it will also feed on various sea anemones and tunicates, and even pieces of squid and mussel. In the laboratory, this species can even be raised on fish food pellets!

Possibly due in part to the ease of keeping it well-fed in an aquarium, Hermissenda crassicornis has become a laboratory animal model for research on the neurobiology of learning and memory, and can also be readily cultured in captivity, with the newly hatched larvae being raised on planktonic algae. Some examples of studies which focus on this slug can be seen here.

Thus Hermissenda crassicornis would seem to be the perfect nudibranch for a home aquarium. It's colourful and attractive, and it won't slowly starve to death in an aquarium. Unfortunately, its range is limited to the North Pacific, including the Pacific coast of North America from Baja California to Alaska, as well as the seas around Japan and the Korean Peninsula. The waters in these areas are certainly not tropical, and it can hence be inferred that while Hermissenda crassicornis would make a colourful and interesting addition to a coldwater marine aquarium, it probably would not do so well in a tropical reef aquarium.

Another species of nudibranch which has been reported to have somewhat indiscriminate dietary preferences (compared to other nudibranchs) is Austraeolis ornata from the coasts of southern Australia; this species has been observed consuming various anemones, stranded jellyfish, and other nudibranch species, and has even taken carrion under captive conditions. Unfortunately, like the preceding species, it too is an inhabitant of temperate waters, and hence is unsuitable for tropical aquaria.

(Photo by Dave Harasti)

Melibe: A NUDIBRANCH SUITABLE FOR THE AQUARIUM?

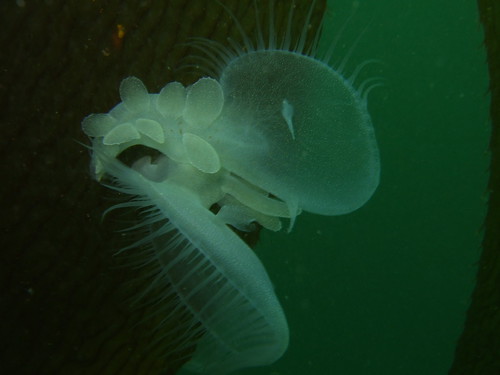

The fourth species of nudibranch exhibited at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in the Kelp Forest exhibit is a very different sort of creature:

Melibe leonina, a predator on tiny crustaceans. (Photo by bswift)

Nudibranchs as a whole are already pretty weird creatures, but those from the genus Melibe are simply downright bizarre.

Melibe sp., Cyrene Reef (Photo by Chay Hoon)

Most nudibranchs, like the vast majority of gastropods, possess a toothed radula, which they use to slowly rasp away at their food. Melibe are unique in that they have actually lost the radula; instead, they possess an expandable oral hood which they use to engulf zooplankton and other tiny marine creatures.

(Photo by Ria)

The oral hood is especially obvious in these Melibe leonina. (Photo by jrixunderwater)

Logically, it would appear that various species of Melibe might be among those nudibranchs that could plausibly survive in an aquarium, provided that there is a regular supply of tiny live prey, such as brine shrimp, mysids, amphipods, or copepods. The technology to culture these crustaceans as live food is already well established.

The brine shrimp Artemia salina, commonly raised as live food for various organisms in the aquarium hobby. Special variants are marketed as novelty pets called 'Sea Monkeys'. (Photo by el viejo)

Like Hermissenda crassicornis, Melibe leonina has been used in laboratories as a model for neurobiology research, with some examples of studies done on this species shown here. Many papers describing work done on captive Melibe, such as this paper, mention that the use of cultured Artemia to feed these nudibranchs. However, this species has yet to be bred in the lab, and so the laboratory animals are made up of adults collected from the sea (this species can be seasonally abundant), with larvae being hatched in the lab from eggs brought in from the wild.

Melibe leonina is another nudibranch that is native to temperate waters off the Pacific coast of North America, from Baja California to Alaska, and so like Hermissenda crassicornis, is not suitable for tropical aquaria. But if the feeding biology of other Melibe species is similar to that of M. leonina, it would be likely that all other species in the genus have the potential to be suitable candidates for aquariums.

However, given that some species of Melibe can grow to quite large sizes, with M. mirifica said to grow more than 30 centimetres in length and M. japonica supposedly reaching 50 centimetres, such huge individuals would require large aquariums, and these might be more than capable of consuming much larger prey than mere brine shrimp.

Melibe ?mirifica (Photo by Ben Naden)

As for suitability for a reef aquarium, presently it appears that no one has deliberately attempted to keep a Melibe within a reef aquarium setup yet, although some aquarists have found Melibe engeli in their aquariums, possibly having stowed away in shipments of live rock.

A captive Melibe will probably need a special tank all to itself, or at least require peaceful tankmates that won't try to eat it, or that it won't try to eat. Another point to consider is whether its tankmates will compete with it for food; the nudibranch might be unable to get its fair share of brine shrimp if all its food is being relentlessly snapped up by fish. In comparison with other nudibranchs, Melibe are not very poisonous, though they do give off noxious secretions that oddly enough, have been reported to smell sweet and fragrant. However, camouflage is their primary means of defence, and if that fails, Melibe will escape predators by actively swimming away (combined with autotomy, or shedding of their cerata). Which might cause some trouble in a reef aquarium, since a swimming Melibe might just blunder right into a large sea anemone or colony of zoanthids and get stung to death, or get sucked up by the filter intake.

At least these nudibranchs do have a decent chance of surviving in an aquarium, even if chances are they have short lifespans anyway. Which is more than can be said about virtually all other nudibranchs sold in the aquarium trade, which are in all respects as good as dead once removed from their natural environments and separated from their prey.

PEST CONTROL NUDIBRANCHS

For some species of nudibranchs, their highly specific diet works to their benefit where it comes to ridding aquariums of unwanted 'pest' species.

It is sometimes very ironic that the desirable corals and sea anemones that one often forks out exorbitant sums of money to purchase can be quite delicate, whereas some species accidentally introduced into the aquarium often do a little too well. Not only can these pests affect the aesthetic value of the aquarium, they can also even affect the health and survival of their tankmates.

(Photo by PhotoByMark)

Glass anemones (Aiptasia spp.) are the bane of the reef aquarist; these unwanted anemones can reproduce so well in aquaria, that they often overwhelm and outcompete other sessile organisms, stinging expensive corals, giant clams, and zoanthids to death. Numerous solutions have been proposed, from physical removal of the anemones to injecting chemicals to kill them, to using predators to control their numbers. All have their advantages and drawbacks; many of the possible predators of glass anemones will also nibble expensive invertebrates in the aquarium.

Once established, Aiptasia can quickly reach plague proportions. (Photo by robertopalmari)

Aeolidiella stephanieae (Photo from Sea Slug Forum)

One tiny species of nudibranch from Florida, Aeolidiella stephanieae is currently being promoted as an effective way to get rid of Aiptasia without threatening other aquarium inhabitants. This is one of those species which is able to retain and use the zooxanthellae from its prey, which is predominantly if not exclusively composed of Aiptasia. However, the zooxanthellae alone cannot sustain the nudibranch indefinitely, so it has to feed often. Because nudibranchs in general are so particular about their food, the claims that this species can be a reef-safe and effective means of Aiptasia control appear to be accurate. Their prey is extremely easy to culture in captivity, and so are the nudibranchs themselves.

Aeolidiella stephanieae laying eggs (Photo from Reefkeeping)

Swarm of juvenile Aeolidiella stephanieae feeding on Aiptasia. (Photo from Berghia.net)

Many nudibranch species have a planktonic larval stage, where the newly hatched young float about in the plankton, feeding on various other planktonic organisms. Hermissenda crassicornis and Melibe leonina, discussed earlier, are among them. This need to keep the planktonic larvae alive is often the greatest hurdle to successfully breeding many marine animals in captivity. However, Aeolidiella stephanieae has a very short non-feeding planktonic larval stage; these larvae quickly metamorphose into miniatures of the adults, ready to feed on Aiptasia. Once established in an aquarium, a single pair of Aeolidiella stephanieae can quickly form a small breeding colony that continues to propagate itself as long as Aiptasia are present.

An example of a simple and inexpensive setup to culture Aeolidiella stephanieae. (Photo from Reefkeeping)

The catch though, is because they are so small, stocking them in insufficient numbers in large aquaria may mean that the nudibranchs quickly consume all the Aiptasia in the immediate vicinity, then starve to death before they manage to consume the last remaining Aiptasia elsewhere in the tank, which will then quickly proliferate once again in the absence of their predator. They may also be vulnerable to predatory tankmates such as fish, shrimp and crabs, many of which will not be able to resist such bite-sized morsels.

Pair of Aeolidiella stephanieae attacking Aiptasia (Photo from Conscientious Aquarist)

Many websites discussing the use of these nudibranchs as pest control encourage buyers to culture Aiptasia in a separate container so as to provide a continuous food supply. This way, one can maintain a ready stock of nudibranchs on standby to combat future blooms of Aiptasia in the main aquarium. An alternative is to remove the nudibranchs with a pipette once they've done their job and pass them on to a friend who needs them.

There is some confusion regarding the species used to control Aiptasia in aquarium; the species Aeolidiella stephanieae was described only in 2005. Prior to that, this species was marketed as Berghia verrucicornis, which is a completely different species known from the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. Thus many of the articles discussing the captive care and propagation of Berghia verrucicornis, such as seen here, here and here, are actually referring to Aeolidiella stephanieae. And in fact, as this link shows, it is possible that more than one species is actually being sold and researched under the name of Berghia verrucicornis.

Spurilla major (Photo taken by * Alicia)

Another species that has been cultured and marketed as a predator of Aiptasia is the Indo-Pacific species known as Berghia major. However, like Aeolidiella stephanieae, this species apparently does not belong to the genus Berghia, and is now known as Spurilla major.

Spurilla neapolitana (Photo by jordirs123)

Another species, Spurilla neapolitana from the Mediterranean, western Atlantic, and eastern Pacific, has also been recorded to consume Aiptasia in the aquarium. An article on the care and breeding of this species in the aquarium is available here.

Two Spurilla neapolitana feeding on Aiptasia. (Photo from Reefkeeping)

Spurilla neapolitana also feeds on majano anemones (Anemonia majano), another undesirable anemone species that will sting other invertebrates in the aquarium. (Photo from Reefkeeping)

Chelidonura varians, a predatory cephalaspidean slug. (Photo by Erwin Kodiat)

Another slug that one may find in the aquarium trade being promoted as pest control is Chelidonura varians from the Indo-Pacific. This is a predator that feeds on small acoel flatworms (usually Convolutriloba retrogemma), which can quickly become a harmless but unsightly plague in the aquarium.

However, despite this name, it is not a nudibranch, but instead belongs to a closely related group of gastropods known as the headshield slugs. That has not prevented tragedy from occurring, like this person who ordered Chelidonura varians, but instead ended up receiving the nudibranch Chromodoris annae. Needless to say, these nudibranchs are most likely going to slowly starve in the aquarium. This problem is likely exacerbated by the fact that like all other sea slugs, Chelidonura varians is sometimes marketed as a nudibranch, under the name of 'blue velvet nudibranch', when it is not a nudibranch.

Coming up, nudibranchs can find their way into aquariums, as stowaways and hitchhikers. Is this a good or a bad thing? What can you do as a responsible aquarist?

This is part 4 of a 5-part series on nudibranchs, inspired by a feature article on nudibranchs on the National Geographic website.

Part 1: Nudibranchs are beautiful

Part 2: What is a nudibranch?

Part 3: Are nudibranchs suitable for aquariums?

Part 4: Nudibranchs for the aquarium (this post)

Part 5: Nudibranchs: Stowaways and Hitchhikers