(Update 19th March 2013: A paper with details about the behaviour and movements of the small flock of Asian openbills in Singapore has just been published in Nature in Singapore)

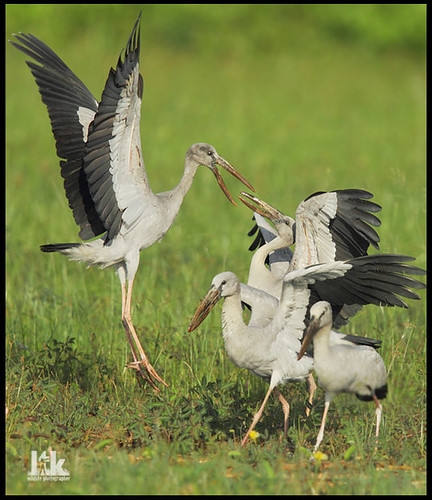

Asian openbills, Seletar West Link;

(Photo by ltk2505)

The Asian openbill typically inhabits wetlands further north, from India and Sri Lanka to Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. However, like many other large birds, it is capable of dispersing over great distances. Recent records in the Malay Peninsula were unknown until a single bird was seen in March 2008 in Chuping, Perak. There were no further sightings in Peninsular Malaysia until January 2010, when another individual was recorded from Permatang Nibong, Penang, and subsequently joined by several others. Small numbers of Asian openbill were seen again in Penang later that year, and they reappeared the next year, in February and August.

It's possible that the species has been slowly spreading south, with this recent incursion into Malaysia representing an expansion of wintering range. This year's appearance of the Asian openbills turned to be quite spectacular.

Large numbers of Asian openbills were seen in Phuket in late December 2012, far south of their usual breeding range in central Thailand.

Asian openbills, Phuket;

(Photos by Tommi Koppinen)

On 8th January, Asian openbills were seen at multiple locations in Peninsular Malaysia:

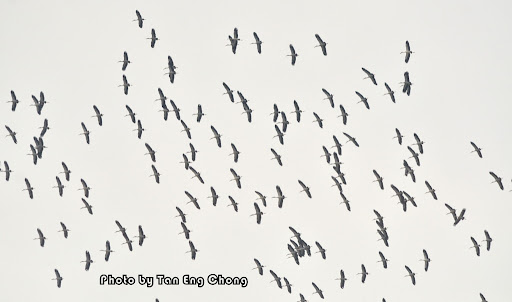

A massive flock estimated to number approximately 1,000 individuals was seen above Kuala Gula, Perak.

Flock of Asian openbills above Kuala Gula;

(Photos by Tan Eng Chong)

An estimated 300 birds were also seen soaring above Penanti, Penang, that same morning.

The next day, around 240 Asian openbills were seen in Batang Tiga, Melaka.

(Photos by Ooi Beng Yean, shared by Malaysian Nature Society)

A small group of Asian openbills returned to their old haunts at Permatang Nibong. Perhaps some of these were birds that had previously fed and roosted here back in 2010 and 2011.

Asian openbills, Permatang Nibong;

(Photo by Choy Wai Mun)

However, many Asian openbills apparently chose to settle in Batang Tiga for the time being, resulting in many birdwatchers from all over Malaysia and Singapore flocking to the ricefields for a glimpse of a species previously unrecorded from the southern Malay Peninsula.

Asian openbills, Batang Tiga;

(Photos by Mohammad Rosmadi Hassan)

It appeared that some of the Asian openbills continued to move south, as another large flock was seen at Teluk Rimba, Johor, on 20th January.

Asian openbills, Teluk Rimba;

(Photos by Vincent Chow)

It was probably only a matter of time before the Asian openbills arrived in Singapore.

At least 8 birds were seen at Pulau Punggol Barat on 22nd January, while 6 were spotted at the nearby Seletar West Link on 23rd January.

(Photos by NatureInYourBackyard)

(Photo by myrontay)

(Photo by ltk2505)

(Photos by Chye Guan, Tan)

(Photos by See Toh Yew Wai)

(Photos by allnt)

Samson has more photos of the Asian openbills over at his blog, as does Lim Cheow Tin over at the Nature Photographic Society, Singapore forum.

Andy also recorded video footage of the openbills looking for breakfast.

The Asian openbills did not remain in Singapore for long; they vanished after a few days, presumably having flown elsewhere. Perhaps they turned around and headed back north, and rejoined their counterparts in Malaysia. Or did they push on south and head towards Sumatra?

(Update 12th February: According to comments from others on the BirdingSingapore Facebook group, at least 4 birds are still present in the same area)

(Update 22nd March: Word is that the openbills left their roosting and feeding sites in Seletar on 11th February or thereabouts, but have since been seen sporadically in Woodlands and along the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE). Their new roosting site remains unknown)

Besides this small flock at Seletar, a single individual had been sighted over Neo Tiew Lane, and a number had been seen in flight over Jurong Island.

While it may be a little disappointing that the large flocks seen at Batang Tiga and Teluk Rimba did not turn up here, it's still very exciting to have a new species added to the checklist, especially one that is so large and distinctive. Not to mention that these storks had been seen by multiple people, with many high-quality images captured and shared online; the veracity of this record is not in doubt.

But there is one question: why did so many Asian openbills suddenly show up so far south of their usual breeding range? Unlike some other stork species, this species is largely sedentary and does not usually undertake long migrations, although it may range far and wide in response to weather patterns or availability of food. There are no known fixed migratory routes; instead, any movement beyond the usual breeding range is quite random and subject to the individual bird's whim and fancy. At the same time, juveniles are known to disperse erratically after fledging, and adults are likely to do the same outside of the breeding season. Indeed, the birds encountered in Malaysia and Singapore appear to be mostly juveniles, with some adults in non-breeding plumage.

Nesting colony of Asian openbill, Orissa, India;

(Photo by Ranjit Sahu)

It is possible that numbers in the breeding colonies in Thailand have expanded to the point that some birds are fleeing overcrowding and dispersing further afield, perhaps in search of new places to feed, roost, and possibly even breed. Or maybe it's related to the Asian openbills' primary food source: snails.

In recent decades, various species of American apple snails (Pomacea spp.) have become established in wetlands and ricefields in many parts of Southeast Asia. Initially introduced as a potential source of food and income for rural communities, these aquatic snails soon managed to spread and multiply, becoming serious agricultural pests, as well as possibly competing with native apple snails (Pila spp.).

Channelled apple snail (Pomacea ?canaliculata) laying eggs;

(Photo by crookrw)

Egg masses of channelled apple snail;

(Photo by Ms Haremones)

The burgeoning populations of invasive snails in Thailand and elsewhere in Indochina have probably benefited the openbills, which feed mainly on molluscs such as snails and freshwater mussels, although they have also been recorded feeding on worms, crabs, and frogs. Given that these non-native snails are now widespread and very abundant in various freshwater ecosystems in Malaysia and Singapore, might this be another factor that attracted the large flocks of openbills? Or was there some sort of human disturbance or severe weather phenomenon further north that led to a mass exodus? Hopefully, the Thai birding community might be able to provide some clues.

It is this diet of snails that apparently explains the unique appearance of the Asian openbill and its relative, the African openbill (Anastomus lamelligerus). Even when the beak is closed, there is a gap between the upper and lower jaws.

Asian openbill, Kaziranga, Assam, India;

(Photo by Lip Kee)

When a snail is seized, the openbill inserts the tip of its curved lower jaw into the aperture of the shell, and separates the snail's body from its shell. Contrary to older sources which claimed that the openbill used its unique beak like a nutcracker to crush its prey, the shells of snails consumed by openbills remain more or less intact. The gap, and the converging tips of the bill, probably enable the openbill to get a more secure grip on the smooth, rounded shells of its mollusc prey, as well as to apply greater force to extract the snail from its shell.

Asian openbill feeding on snail, Mae Wong, Thailand;

(Photos by gary1844)

Oddly enough, the gap is found only in adult birds, but juveniles appear to be capable of feeding on snails as well. It would be interesting to see if adults are better equipped to handle larger snails than juveniles, with biomechanical studies to analyse the entire feeding process.

Asian openbills foraging, Yala, Sri Lanka;

(Photo by Rainbirder)

Other storks of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore

This might represent the first record of Asian openbill in Singapore, but it's not the first species of stork that has been spotted here in the wild.

Last year, I wrote a post about how the neighbourhood of Serangoon might have been named after the lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus), the only species of stork ever thought to be native to Singapore. Although the lesser adjutant is now locally extinct, occasional sightings in the Western Catchment suggest that it's best regarded as a non-breeding visitor.

Lesser adjutant, Johor;

(Photo by Lip Kee)

Recently, on 28th January, David Li saw a small group of lesser adjutant somewhere near Pulau Pergam, off the northwestern coast of mainland Singapore. For now, it appears that they're merely visitors from Johor, although it would be a thrill to have them breeding in Singapore once again.

Lesser adjutant in Singapore;

(Photo by David Li)

In Peninsular Malaysia, the lesser adjutant has suffered a considerable decline in numbers, although it can still be found in the mangroves and mudflats of the west coast, such as Kuala Gula in Perak, Kuala Selangor in Selangor, and Parit Jawa in Johor.

Lesser adjutant, Kuala Gula;

(Photo by Zakir Hassan)

Besides the lesser adjutant, I also noted that 2 other species of stork are now found in Singapore, the milky stork (Mycteria cinerea) and painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala). Introduced by the Singapore Zoo, free-flying flocks of both species of stork are regularly seen in surrounding areas, with some storks even feeding at Sungei Buloh and Jurong Lake.

Milky stork, Japanese Garden;

(Photo by kampang)

Painted stork, Sungei Buloh;

(Photo by Brandon)

The status of these 2 species in Peninsular Malaysia is a little complicated. The milky stork was once found in mangroves and mudflats along nearly the entire west coast of the peninsula, from Kedah to Johor. However, it suffered a precipitous decline, and vanished from most areas, with a final refuge in the Matang Mangrove Forest in Perak. Between 1984 and 1989, the milky stork population there was thought to number approximately 130 to 150 individuals. Despite repeated attempts, the storks failed to successfully raise young, and this small flock continued to dwindle over the years. A 2004 survey recorded only 9 individuals. And in an even more recent study in 2009, less than 5 individuals were observed in the wild at Matang, while only a single bird was spotted in 2010.

Milky storks, Matang;

(Photo by Tiomanese)

To help reverse this depressing state of affairs, and prevent the milky stork from becoming locally extinct as a resident breeder in Malaysia, a captive breeding and reintroduction programme was developed, in the hope of establishing free-flying breeding populations elsewhere.

In 1998, a group of 10 milky storks from Zoo Negara were housed in an on-site aviary at Kuala Selangor Nature Park, with the first reported nesting taking place in March 2002. Between 2002 and 2003,6 nesting attempts were made, but no young survived to fledge. After a single bird escaped through a tear in the netting in April 2003, the decision was made to release all the birds from the aviary shortly after. Courtship and nest-building outside of the enclosure soon began, with 3 milky stork nests built in the midst of a grey heron colony. 6 eggs were laid, of which 5 hatched. Only 2 of the hatchlings survived beyond the first couple of days, but disaster struck when a storm in July toppled the nest, killing the chicks. The entire flock left the park at the end of July, although 4 individuals were known to inhabit nearby Sungai Buloh in 2005, and at least 5 milky storks were seen back at Kuala Selangor Nature Park on a regular basis until 2007. I have not been able to find any information on recent sightings of milky stork in the Kuala Selangor area; whether they have settled in the mudflats and mangroves along the coast, or whether the flock has died out or simply left the area, is not known.

A second reintroduction attempt has been made at Kuala Gula, with 8 captive-bred milky storks released in 2007. Between then and 2011, a total of 36 milky storks were released, although there does not seem to be any information as to whether these storks have managed to breed.

Milky stork, Kuala Gula;

(Photo by summerboat)

Milky storks might have inadvertently been introduced elsewhere in Perak in 2004. The Taiping Zoo once had a flock of 14 birds that were not caged as their flight feathers had been clipped to prevent escape. However, in what must have been a case of negligence or carelessness, the flight feathers were not trimmed regularly, and they grew back, allowing the storks to simply fly off. There are no reports as to whether these escapees might have turned up elsewhere.

Further south, sightings of milky storks near Johor Bahru are likely to represent visitors from the free-flying flocks at the Singapore Zoo. Other sightings might possibly be of birds that have wandered over from Sumatra, which remains a stronghold for this species for now.

Milky stork, Zoo Negara;

(Photo by andrewsohkeemeng)

Milky stork, Singapore Zoo;

(Photo by anjajessen)

At the beginning of the 20th century, the painted stork was recorded from Langkawi, was known to disperse in small numbers from breeding colonies in southern Thailand into the northern states of Perlis and Kedah, and was also vagrant further south to Kuala Lumpur. Today, however, any sightings of supposedly wild painted storks in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore are of captive origin.

For instance, large numbers of painted storks are often seen in and around Kuala Lumpur; these are free-flying birds from Zoo Negara. Some of these have even settled down and formed a breeding colony at the Putrajaya Wetlands.

Painted storks, Zoo Negara;

(Photo by NaNaLiL)

Painted storks, Putrajaya Wetlands;

(Photo by spOt_ON)

Similarly, any painted storks seen in Singapore or Johor are almost certainly from the Singapore Zoo.

Nest of painted stork, Singapore Zoo;

(Photo by 9dr7)

Unfortunately, these painted storks complicate the efforts to protect and reintroduce the milky stork. Hybridisation does take place when both species occur together, and the resulting young can bear a close resemblance to 'pure' milky storks. Free-flying painted storks might end up breeding with wild milky storks, leading to genetic pollution, while some milky storks selected for reintroduction efforts might turn out to be of hybrid ancestry. And with such a small population of milky storks in Malaysia, there is a higher risk that this handful of individuals might inadvertently look for suitable mates among the more abundant painted storks. A few years ago, it was suggested that the free-flying painted storks at Zoo Negara should be taken back into captivity and confined, although this does not seem to have happened.

Milky (L) and painted (R) storks, Sungei Buloh;

(Photo by chrisli023)

The story of the milky stork and its disappearance from much of its range in Peninsular Malaysia illustrates some of the problems that various species of storks (and other wetland birds, for that matter) face in tropical Asia. There is the usual threat of habitat destruction, which results in the loss of feeding or roosting grounds due to development or agricultural conversion. The felling of large trees that storks require for nesting poses problems, forcing the birds to seek alternative sites for nesting colonies. Then there is pollution, which might not only negatively affect the aquatic creatures that the storks feed on, but also accumulate in the bodies of the storks themselves and affect their health. Storks feeding in agricultural areas might inadvertently pick up high concentrations of pesticides. Human disturbance near nesting sites is another possible factor affecting reproductive success, as is uncontrolled hunting of adult storks, and gathering of eggs and nestlings. Today, both the lesser adjutant and milky stork are considered Vulnerable to extinction, while the painted stork is Near Threatened. The Asian openbill faces these same threats, but has made a bit of a recovery in recent years, especially in Thailand. The species is listed as being of Least Concern, possibly because it is not so heavily reliant on mangrove and wetland habitats compared to other stork species, and it is tolerated by farmers as it feeds on apple snails.

Besides these 4 species of stork, birdwatchers in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore might also want to keep an eye out for a few other stork species, which although either rare or extinct in neighbouring Thailand these days, might still show up and spring a surprise.

The nearest known breeding population of greater adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) is in Cambodia, but this Endangered bird was once more widely distributed, from Pakistan and India to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Vagrants are known to visit Thailand, so it's not impossible that this species could wander into the northern states of Peninsular Malaysia.

Greater Adjutant, Bhutan;

(Photo by Lee Hunter)

The black-necked stork (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus) is a species whose populations have suffered greatly, with a total population of possibly less than 1,000 individuals in South and Southeast Asia. In Thailand, it was formerly widespread, although it is now very rare if not already extinct. This species seems to be completely absent from the Greater Sunda Islands, but a skull reported from Java in 1908 suggests that it formerly occurred in the area. Probably the only reason why the black-necked stork is considered 'merely' Near Threatened is due to the presence of larger stable populations further east in New Guinea and Australia.

Black-necked stork, Keoladeo, Rajasthan, India;

(Photo by Lathers)

The woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) is another widespread species, being found across sub-Saharan Africa, as well as from India to Sulawesi, the Lesser Sunda Islands and the Philippines. The only Malaysian records were from the north, in Kedah and on Langkawi, and although it was described in the 1930s as being 'very common in ricefields and plains throughout the northern part of the Peninsula', it seems to have vanished from this area, and has also been extirpated from most of southern Thailand.

Woolly-necked stork, Kaladhungi, Uttarakhand, India;

(Photo by spiderhunters)

Some older references list the woolly-necked stork as being widespread in the Malaya Peninsula, although it is likely that many of them actually refer to Storm's stork (Ciconia stormi), which was once considered to be a subspecies of woolly-necked stork. Storm's stork is restricted to lowland areas, and inhabits freshwater and peat swamp forests on the floodplains of large rivers. An Endangered species that still survives in Peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand for now, the core of its population is in Sumatra and Borneo; it is estimated that only 250 to 500 mature individuals remain in the entire world.

Storm's stork, Bilit, Sabah;

(Photo by GARY ALBERT NATUREPIX)

The plight of the storks of South and Southeast Asia is identical to that faced by many other birds that utilise wetlands in the region, such as grebes (F. Podicepedidae), cormorants (F. Phalacrocoracidae), darters (F. Anhingidae), herons, egrets and bitterns (F. Ardeidae), pelicans (F. Pelecanidae), ibises (F. Threskiornithidae), finfoots (F. Heliornithidae), cranes (F. Gruidae), rails (F. Rallidae) and ducks and geese (F. Anatidae). Some species are more resilient to human impacts than others, and remain common, while others have suffered great declines and vanished from large portions of their former range.

While it is encouraging to see the conservation efforts in many countries to restore critical wetland habitat and protect nesting colonies, one does wonder if the flocks will ever regain their former glory. What was it like to stand in a marsh in Siam, or a mangrove in Perak, or a ricefield in Kedah, back in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and watch the waterbirds?

Perhaps someday, if we continue to protect important nature areas and other green spaces from development, and seek to restore the formerly interconnected network of mangrove and mudflat habitats that once lined our northern shores, the lesser adjutant will return here to breed. The milky storks of the Singapore Zoo might spread further and form the nucleus of a new breeding population in the Singapore-Johor area. And with luck, one day, we might look up at the skies over Seletar, and see more than a hundred Asian openbills deciding to drop by for a visit.