Today is World Animal Day. All around the world, various events are being held to celebrate and acknowledge the intricate relationships between us and the other animals.

Today is World Animal Day. All around the world, various events are being held to celebrate and acknowledge the intricate relationships between us and the other animals. Locally, the Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES) decided to commemorate World Animal Day by focusing on a single issue, the overexploitation of sharks for their fins, which are incorporated into shark fin soup, a dish traditionally considered to be a luxury item.

However, the growing affluence of ethnic Chinese in many countries has meant that demand for shark fins has skyrocketed, inadvertently leading to overfishing and overharvesting of sharks for their fins. The cruelty of hacking the fins off a live shark aside, current rates of exploitation are almost certainly unsustainable.

Eight Steps to a Bowl of Shark's Fin Soup

Casualty of shark finning, Raja Ampat;

(Photo by Thierry Minet)

Shark fins, Hong Kong;

(Photo by alvin__)

Shark fins, Brazil;

(Photo by seashepherdbrasil)

Given that sharks are long-lived creatures that reproduce at very slow rates, this seemingly insatiable greed for shark fins has widespread and long-lasting ramifications for shark populations worldwide; once fished to the point of commercial extinction, it will take a very long time for numbers to rebound. As apex predators, this has profound implications for marine ecosystems; as large predators are removed, trophic cascades are created, affecting the numbers and even behaviour of prey, with wider implications for an entire host of species.

Shark Finning: Unrecorded Wastage on a Global Scale

Casualty of shark finning, Raja Ampat;

(Photo by Justin Ebert)

Perhaps the most well-known example has involved the decline of several species of so-called 'great' shark off the eastern seaboard of North America. These larger shark species have experienced steep declines in their numbers, due to overfishing and unintentional capture as bycatch; for example, blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus) have declined by 93%, tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) by up to 97%, 98% for scalloped hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini), and by 99% or more for bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas), dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus), and smooth hammerheads (Sphyrna zygaena).

Scalloped hammerhead, Costa Rica;

(Photo by pats0n)

Bull shark, Mozambique;

(Photo by wirodive)

This has in turn affected the populations of their prey, in particular various species of smaller sharks, rays and skates. As the larger shark species have declined and become functionally extinct across large areas, so the numbers of these smaller elasmobranchs, which used to be preyed upon by the larger sharks, have boomed. The population of one species in particular, the cownose ray (Rhinoptera bonasus), has increased by an order of magnitude to more than 40 million individuals.

Left: Cownose ray, Shedd Aquarium;

(Photo by DrawingOnSculpture)

Right: Cownose rays, Panama;

(Photo by Art Wolfe)

These smaller sharks, skates, and rays are mesopredators, smaller predatory species which occupy mid trophic levels, preying on species further down the food web, while at the same time being preyed upon by the apex predators. Cownose rays feed predominantly on bivalves, including several commercially important species. With the removal of the 'great' sharks that used to control cownose ray numbers, ray populations have exploded, and consequently led to decimation of some of the bivalves they feed on; as a result, the century-old bay scallop fishery (Argopecten irradians) in North Carolina has been closed since 2004.

Bay scallop, Connecticut;

(Photo by Seaweed Lady)

Another important species, the hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) or quahog, has also been greatly affected by this increase in cownose ray numbers, and in a bizarre yet horrifying turn of events, this has resulted in clam chowder, a signature dish along the Atlantic seaboard, being pulled off menus as hard clam harvests nosedive.

Hard clams, Washington D.C.;

(Photo by Littoraria)

It's not just scallops, clams, and seafood lovers that are affected by the loss of sharks. As the rays root around in the seabed for their buried prey, they inadvertently uproot seagrass beds; 40 million cownose rays must have a profound impact on seagrass ecosystems all along the east coast, which will consequently affect nursery grounds for all manner of other species. Also, clams play a significant role in filtration, removing vast quantities of phytoplankton from the water, and improving water quality. Their decimation may pave the way for more frequent, more massive algae blooms, further stressing vulnerable coastal ecosystems.

Baum, J. K., Myers, R. A., Kehler, D. G., Worm, B., Harley, S. J. & Doherty, P. A. 2003. Collapse and conservation of shark populations in the Northwest Atlantic. Science, 299(5605), 389-392.

Myers, R. A., Baum, J.K., Shepherd, T. D., Powers, S. P. & Peterson, C. H. 2007. Cascading Effects of the Loss of Apex Predatory Sharks from a Coastal Ocean. Science, 315(5820), 1846 - 1850.

Brierley, A.S. 2007. Fisheries Ecology: Hunger for Shark Fin Soup Drives Clam Chowder off the Menu. Current Biology, 17(14), R555-R557.

Another important example of how sharks can have a significant role in maintaining the health of marine ecosystems is seen in Shark Bay, Australia. Here, tiger sharks are the dominant predators, and prey heavily on dugongs (Dugong dugon) and green turtles (Chelonia mydas). These 2 species feed heavily on seagrasses, and are forced to change their selection of feeding sites in order to reduce the risk of predation.

Tiger shark, Bahamas;

(Photo by Ken Bondy)

The most nutritious forage is found in shallow areas in the middle of large seagrass meadows; however, this is also where escaping from a hungry tiger shark can be difficult. When tiger sharks are present, dugongs stick to lower-quality forage at the edges of the seagrass patches in deeper water, where they are better able to swim off if attacked. By forcing dugongs to change their feeding habits, tiger sharks indirectly affect the composition and structure of seagrass communities in Shark Bay.

Dugong feeding on seagrass, Red Sea;

(Photo by Ruth and Dave)

In the presence of tiger sharks, healthy green turtles prefer to feed close to the edges of these same patches, where the forage is lower in quality but the risk of successful predation by a tiger shark is lower. On the other hand, sick or injured turtles take a big risk by choosing to feed on the higher quality seagrass in the middle of the patches. Just like with dugongs, tiger sharks alter the feeding behaviour of green turtles, preventing overgrazing of the seagrass and maintaining the health and integrity of the seagrass meadows.

Green turtle feeding on seagrass, Red Sea;

(Photo by Arne Kuilman)

Wirsing, A. J., Heithaus, M. R. & Dill, L. M. 2007. Living on the edge: dugongs prefer to forage in microhabitats that allow escape from rather than avoidance of predators. Animal Behavior, 74(1), 93-101.

Wirsing, A. J., Heithaus, M. R. & Dill, L. M. 2007. Fear factor: do dugongs (Dugong dugon) trade food for safety from tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier)? Oecologia, 153(4), 1031-1040.

Heithaus, M. R., Frid, A., Wirsing, A. J., Dill, L. M., Fourqurean, J. W., Burkholder, D., Thomson, J. & Bejder, L. 2007. State-dependent risk-taking by green sea turtles mediates top-down effects of tiger shark intimidation in a marine ecosystem. Journal of Animal Ecology, 76(5), 837-844.

These are just 2 studies contributing to a growing pile of data that indicates just what sort of consequences may occur when large predators are removed from an ecosystem. These apex predators are often targeted for deliberate removal and eradication, and are usually among the first species to be eliminated from a habitat that is heavily impacted by human activity. It certainly raises a lot of questions about the health of Singapore's own marine ecosystems, where large sharks are more or less all but extinct. Are our reefs, sandflats and seagrass meadows truly healthy, or are we seeing habitats in a slow decline, clamouring for the restoration of the keystone species that once helped keep them in a state of equilibrium? The same question can be asked of many other Asian countries, where shark populations have greatly declined, no doubt partly due to the demand for shark fin.

Predators as Prey: Why Healthy Oceans Need Sharks

When Sharks Die, the Oceans Die

And so, the global overexploitation of sharks, for which the Chinese taste for shark fin must take some blame, not only affects shark populations, but is in fact a serious threat to the health of our marine ecosystems. Given how heavily dependent we are on the oceans for food, the deterioration of our food supply simply because too many of us were unwilling to halt our greed for a perceived delicacy is a thought that is honestly, too frightening to contemplate.

Already, much of our supply of shark fins comes from fisheries in Latin America, and in the past, European fisheries were a major supplier for Asian markets. Singapore is a major centre in shark fin trade and consumption, and as consumers, it certainly is within our power to refuse to contribute to this excessive and unnecessary depletion of shark populations.

Shark finning, Raja Ampat;

(Photo by Justin Ebert)

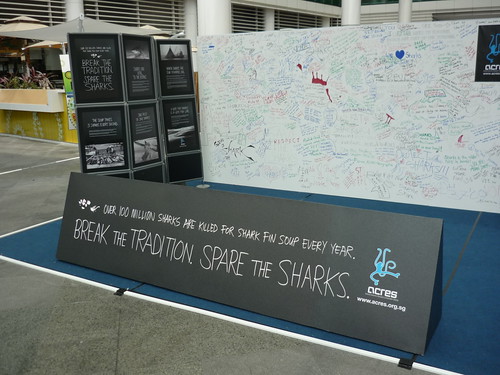

Much effort has been devoted towards changing the mindsets of Singaporeans, and some progress has certainly been made. For World Animal Day this year, ACRES is helping to raise awareness and encourage more Singaporeans to speak up about the decimation of sharks by holding a very unique event, called Break the Tradition. Spare the Sharks.

Since Friday, the 2nd of October, ACRES has been at the Atrium@Orchard, encouraging people to make a stand against consumption of shark fin soup in a rather unique and attention-grabbing way.

Here are the details on the Facebook event page:

When was the last time you were encouraged to break things?

ACRES is inviting everyone to come into town to smash a soup bowl against a wall. The broken pieces will be used on the spot to create a work of art — a gigantic, 15m long mosaic of a shark.

As many as 100 million sharks are killed every year, and most of them end up in soup bowls across Asia. The shark fin soup tradition is wasteful and destructive, because when sharks die, the entire marine food chain also collapses.

So this 'World Animal Day' weekend, we are asking you to symbolically break this habit and send a message to the world that sharks are more valuable than soup.

You will be asked to donate $2.00 for each soup bowl, and the proceeds will go towards ACRES' education and animal welfare efforts.

So come down to The Atrium@Orchard (beside Plaza Singapura) on the first weekend in October, to show that you care about animals, the environment and about leaving our marine legacy for future generations.

You'll be smashing bowls, breaking traditions and making an important statement — all at once.

I was feeling particularly upset and frustrated over certain things going on in my life, so I felt that it would be a good way to relieve my stress while at the same time, contribute to the cause in my own little way.

The booth covered a large area, and was difficult to miss.

There were panels explaining the impact of overfishing of sharks.

As well as a large space where people could write down or draw their thoughts.

People could also get temporary tattoos.

This was where all the action was taking place: a small enclosed area, where people donated money to throw porcelain bowls against a wall.

Much of the space was taken up by this temporary art installation, where the shards and fragments were swept up and used to fill in this huge outline of a shark.

I donated some cash and was given 5 bowls, which I proceeded to hurl against the wall. I have to admit, I'm not normally the sort of person who derives pleasure from breaking things. But channeling my energy into throwing the bowls as hard as possible, and then seeing them shatter into countless tiny fragments, made me feel a lot better.

I managed to take a couple of photos of other people in action.

They were also selling T-shirts and badges to promote the cause.

Breaking a bowl certainly is more of a symbolic gesture than anything else. Cynics might point to the apparent waste of resources. Why break a perfectly good bowl just to make a statement? Surely there are other ways in which awareness can be raised without resorting to such actions?

I do agree to a certain extent with such concerns. Initially, when I heard about this event, I was wondering whether there was a point in expending so much resources. At the very least, manufacturing and transporting those bowls used up precious resources, and going to all the effort just to break them might seem unnecessary to some. Even if it does attract a lot of attention and raise awareness, how many of those people who donated will actually walk the talk and abstain from consuming shark fin soup in future? How many of them are merely paying lip service to conservation?

Yet, the optimist in me likes to think that thanks to this event, there are people out there who have become more aware about this serious issue, and will take an active effort in reducing or even completely eliminating their own consumption of shark fin. True, it might seem that this is just another publicity campaign that won't have much of an impact on shark fin consumption in Singapore, but there's no harm in doing all it takes to make sure that as many people as possible know about the threats posed by overfishing of sharks. Hopefully, thanks to this campaign and others, more and more people will come to understand how each of us has a part to play in helping to sustain marine biodiversity, by changing our consumption habits. Surely, if we can abandon the use of tiger bone, bear bile and rhinoceros horn in traditional Chinese medicine, we can wean ourselves away from seeing shark fin as a status symbol and delicacy?

The perception that shark fin soup is some rare and expensive delicacy in Chinese culture is frankly, one that is probably as relevant as foot-binding is today. Perhaps, in the past, when shark fin was more difficult to obtain, and when it was a dish few people could afford, the threat posed to shark populations and the health of marine ecosystems was not so great. But with rising affluence, and when the value of shark fin has become so cheapened that you can buy canned shark fin at the supermarket, and order it for $2 or so at the pasar malam, why do people still cling to this outdated and ecologically ignorant notion that omitting shark fin soup at a wedding banquet is somehow a loss of face?

In light of what we know about the world around us, some traditions are better off being discarded and broken.

Here's the press release from ACRES about the event.