STOMPer Angler was enjoying a stroll along the beach at Pasir Ris when he spotted a giant jellyfish that had washed ashore. Where did it come from, he wondered.

Said Angler in his contribution (Apr 26):

"Giant jellyfish at Pasir Ris beach?

"These pictures were taken at the beach at Pasir Ris Park near Sungei Api Api.

"I was walking along the sandy beach when I came across this mysterious giant jellyfish that was washed ashore by the tide.

"As the tide retreated, the jellyfish was left behind on the beach.

"It is about 2 metres in diameter and it was palpitating in a wavy form.

"I am wondering where this giant jellyfish came from.

"Can some marine biologist enlighten me?"

It is incredibly annoying when one sees photos of a supposedly large dead animal on the beach, yet the photographer fails to provide another object for scale. Based on the photos alone, there is no way to tell how large this jellyfish is. Is it 2 metres in diameter? 1 metre? 20 centimetres? 2 centimetres?

Would it kill you to put something next to it for comparison? Few people have a measuring tape with them all the time, but I'm sure placing a foot or hand next to the jellyfish would give some clues as to how large it is. I'm willing to believe that this is a very large jellyfish, as they are found from time to time in our waters, but in the absence of at least some idea of its size, I will not accept the claim that it is 2 metres in diameter.

Giant jellies on our shores

Huge jellyfish, Changi;

(Photo by Ria)

Every once in a while, very large jellyfishes can be seen in the waters off our northern shores. They're hardly the 2-metre monsters as stated in the original post on STOMP, but the bell can grow from 25 to 50 centimetres in diameter, which is very large indeed. They appear to be seasonal, which is something we find with many of our local jellyfishes; months pass without a single sighting, then we suddenly find them everywhere, and then the jellyfish mysteriously vanish after some time. We still do not know the identity of the this mysterious giant jellyfish, or whether all the specimens we have found are of the same species in the first place.

Changi;

(Photo by Melvin Chia)

Changi;

(Photo by Ria)

Chek Jawa;

(Photo by Ms Haremones)

Unfortunately, I cannot find any photos that show these jellyfish floating gracefully in the water, instead of being stranded on the shore and looking pretty much like a saggy gelatinous blob of jelly.

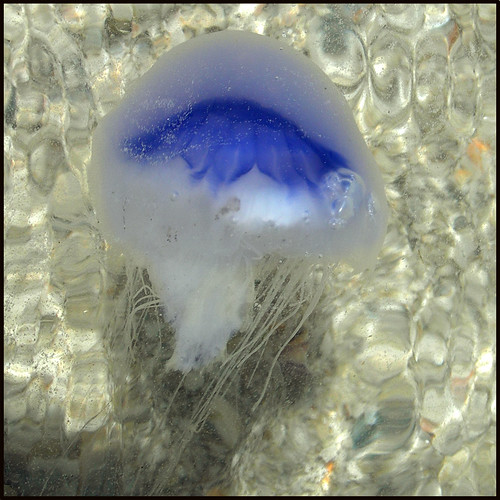

A very different sort of jellyfish found in Singapore gets to quite large sizes; this is the blue lion's mane jellyfish (Cyanea lamarckii). However, the only record I know of comes from West Coast in 1987. This specimen is currently on display at the Public Gallery of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research.

Blue lion's mane jellyfish, North Sea;

(Photo by ESOX LUCIUS)

The taxonomy of this specimen is currently not quite settled; the western Pacific population of lion's mane jellyfish is now considered to be a different species, Cyanea nozakii, which may have some bearing on the identity of the specimen in the RMBR.

Jellyfish Diversity

Singapore's jellyfishes have not been studied in detail, so it is hard to identify them with any level of certainty. However, we have been able to make tentative identifications, thanks to Dr. Michael N. Dawson.

Ribbon jellyfish (Chrysaora sp.), Pulau Hantu;

(Photo by Debby)

Upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea sp.) upperside, Pulau Semakau;

(Photo by Ria)

Upside-down jellyfish underside, Terumbu Raya;

(Photo by Marcus)

There are several species of jellyfish that look similar to one another; these belong to the family Catostylidae.

Catostylus sp., Changi;

(Photo by Ria)

Acromitus sp., Sungei Buloh;

(Photo by Ms Haremones)

Ria has taken photos of a few other jellyfish species which we have not been able to identify yet.

Terumbu Bemban;

Terumbu Bemban;

Tuas;

Keppel Bay Marina;

This last jellyfish looks a lot like the spotted jellyfish (Mastigias papua), which has a wide distribution in coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific. It is also the species that gave rise to the famous inhabitants of the lakes of Palau.

Spotted jellyfish, Tanzania;

(Photo by algaedoc)

Swarm of jellyfish in Jellyfish Lake, Palau. These are descended from the spotted jellyfish and are known as golden jellyfish;

(Photo by T. Chen)

Dr. Dawson also shared with Ria how to photograph jellyfishes for identification. He used to run The Scyphozoan, a site dedicated to the jellyfish biology and diversity. The site's latest incarnation is The Scyphozoan Wiki.

Scypho-, Cubo-, Stauro-, Hydro-

Scyphozoa is the name of the group of cnidarians that encompasses most known jellyfish species. There are 2 other smaller groups of cnidarians we commonly call jellyfish, the Cubozoa (box jellyfishes) and Staurozoa (stalked jellyfishes). These 2 groups used to be considered part of Scyphozoa, until they were split away, hence the scyphozoans are sometimes known as "true" jellyfish.

The stalked jellyfishes are unique in that they lead a sedentary lifestyle when adult, living more like sea anemones or coral polyps.

Lucernaria bathiphylla (Staurozoa), White Sea;

(Photo by Alexander Semenov)

The box jellyfishes are infamous for containing a number of species with deadly venom. It is not known if any species inhabit Singapore waters, but it is likely that they are present, given that they are found throughout the region.

Sea wasp (Chironex fleckeri);

(Photo by David Doubilet)

When is a jellyfish not a jellyfish?

Like corals and sea anemones, jellyfishes are cnidarians. Another group of cnidarians known as the Hydrozoa also has jellyfish-like forms. Many species have a sedentary polyp life phase and a mobile medusa (jellyfish) life phase, but there are some that live entirely as medusae.

Crystal jelly (Aequorea sp.)

(Photo by Ria)

There are even 'jellyfish' in freshwater! The freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sp.) is a tiny, harmless member of the Hydrozoa that can be found in freshwater habitats on almost every continent. It has been recorded from fish ponds in Singapore.

Freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbyi)

(Photo by Andreas Werth)

Most of the creatures we call 'jellyfish' are free-living individual organisms. However, they are often confused with the siphonophores, which are actually colonies made up of many different specialised individuals known as zooids. Very little is known about siphonophores in local waters, although it is believed that the most well-known species, the Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis), is not found in Singapore.

Portuguese man o' war, Florida;

(Photo by mcmillend)

Another group of animals commonly mistaken for jellyfish are the ctenophores or comb jellies. In fact, these are not even cnidarians at all, but form a distantly-related group. Unlike cnidarians, they do not possess venomous stinging cells. We have encountered them from time to time: ghostly, nearly completely transparent little shapes swimming near the surface, the endless beating of the cilia that line their bodies creating tiny shimmering rainbows.

Beroe cucumis, White Sea;

(Photo by Alexander Semenov)

Giant jellies elsewhere

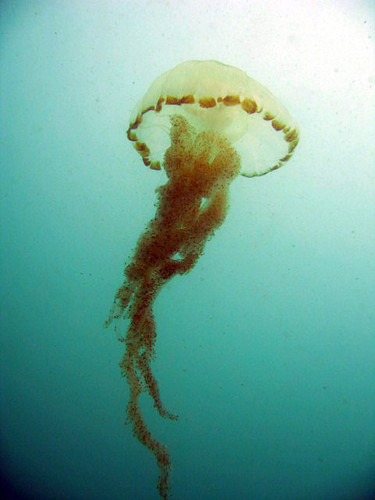

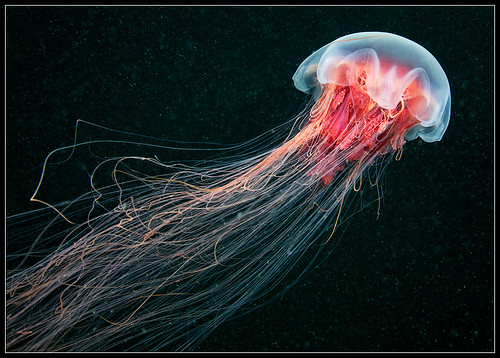

The blue lion's mane jellyfish can get to relatively large sizes, with the biggest specimens possessing a bell 30 centimetres in diameter. It has a much larger cousin, the lion's mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata), which is also one of the world's largest jellyfish species.

Lion's mane jellyfish, White Sea;

(Photo by Alexander Semenov)

A coldwater species found in the northern oceans, the lion's mane jellyfish has an average bell diameter of 35 to 50 centimetres, although there are exceptional records of bells spanning 2 metres. The record is of a giant washed up on the shore of Massachusetts Bay in 1870, which had a bell 2.29 metres in diameter, and tentacles stretching for 37 metres! It is a contender for the world's longest animal, even longer than a blue whale.

Another gigantic species of jellyfish has become quite infamous, not just for its size, but also for appearing in dense swarms. If our local blooms of jellyfish are a cause for concern to some, then the population irruptions of Nomura's jellyfish (Nemopilema nomurai) are truly nightmarish.

(Photo by Lucia Terui)

The Problem With Jellies

Nomura's jellyfish can have bells up to 2 metres in diameter, and weigh up to 200 kilograms each. Found mostly in the temperate seas off China, they used to be occasional visitors in the waters around Japan, save for periodic blooms that saw large swarms riding the currents to Japan.

(Photo by Lucia Terui)

(Photo by Yomiuri Shimbun/AFP/Getty Images, from jules07d)

In the past, such blooms of jellyfish would occur about once every 40 years. Since 2002, however, Nomura's jellyfish have been extremely abundant, with such a surge in numbers becoming a nearly annual phenomenon.

It's a lot like the swarms of (harmless) golden jellyfish in the lakes of Palau, but much larger and scarier.

(Photo from chocolatemarblecheese)

That's not a swarm of jellyfish.

(Photo from chocolatemarblecheese)

THIS is a swarm of jellyfish.

Fortunately for beachgoers, divers and fishermen, the sting of Nomura's jellyfish is supposedly painful but not life-threatening.

(Photo by Lucia Terui)

(Photo by Lucia Terui)

Whenever these blooms occur, the masses of giant jellyfish bring bad news for the Japanese fishing industry. The jellyfish catch and eat vast quantities of fishes, their eggs and larvae, and when caught in fishing nets, ruin the catch by stinging and crushing the fish. The huge numbers of jellyfish clog and rip nets, and also lead to higher labour costs as time is wasted clearing the jellyfish from the nets, with some fishermen getting stung in the process. There is even an incident in which a trawler capsized after the fishermen on board attempted to haul up a net full of jellyfish.

(Photo from iowaintermedia)

There are many possible causes of such jellyfish blooms. For one thing, climate change and warming seas may play a part; jellyfish grow and breed faster in warmer waters, and seas formerly just a little too cold now provide a hospitable environment. Another likely reason is that overfishing has allowed jellyfish to prosper, by removing potential jellyfish predators, or competitors for food. Some species of sea turtles are important predators of jellyfish, and their decline may have also helped encourage jellyfish numbers to skyrocket. Pollution has a part to play as well; excessive nutrients feed and sustain unprecedented numbers of jellyfish. eutrophication creates low-oxygen dead zones in the sea where jellyfish are able to tolerate better than fish, enabling them to exploit resources with virtually no competition or predators. In some other instances, the jellyfish species that is responsible for the bloom is not native to the area and has become invasive; this is not quite the case with Nomura's jellyfish though.

(Photo by Y.Taniguchi/Niu Fisheries Cooperative, from ScienceImage)

In the case of Nomura's jellyfish, which breed off the coast of China, agricultural and sewage runoff result in nutrient-rich waters that sustain phytoplankton blooms, which in turn support vast quantities of zooplankton that feed the young jellyfish. It also helps that the seas here are heavily overfished. As they grow to adulthood, the jellyfish are carried by the currents towards Japan. Hence, Japan's jellyfish woes illustrate how environmental problems do not respect human constructs such as territorial boundaries, and that resolving these issues will require international cooperation and collaboration.

(Photo by Awashimaura Fisheries Association Cooperative/Reuters, from National Geographic News)

There have been several measures introduced to combat the problem. These include making nets that help screen and separate the fish from the jellyfish, and encouraging locals to eat the jellyfish; there is even ice-cream that includes chunks of Nomura's jellyfish. Unfortunately, from a culinary point of view, Nomura's jellyfish is seen as being of low quality compared to other species of jellyfish.

An interesting solution has been the extraction of a substance found in the bodies of jellyfish known as mucin. Mucin has antibacterial and water-retaining properties, and further research could provide the foundation for development of new medication. Because Nomura's jellyfish is so large, it gives a high yield of mucin, and at least some economic value is derived from the removal and disposal of huge quantities of jellyfish.

This problem with jellyfish blooms appears to be occurring with alarming frequency around the world, and indicates just how human activities have altered marine ecosystems. Whether jellyfish will continue to prosper and eventually so completely dominate the seas that they overwhelm fisheries, or whether the surge will be held in check by natural constraints and human measures of control, it is essential to understand that such population explosions are but mere symptoms of a deeper underlying problem with the way we are managing the oceans.