STOMPer noob was shocked to see an alligator when he went for his usual fishing trip. The reptile was apparently spotted at Sembawang Park.

Said noob in his contribution (Apr 25):

"ALLIGATOR SPOTTED?

"I usually go fishing at Sembawang Park.

"However, what I saw today really shocked me.

"I saw an alligator instead."

This is a post that got me extremely annoyed, for many reasons.

Mistaken Identity

First of all, the crocodilian in the photos is not an alligator. The 2 extant species of alligator, the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) and Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), are not found anywhere near Singapore.

Compared to other crocodilians, alligators tend to have wider, rounded snouts. This is certainly in stark contrast to the reptile pictured, which has a long and narrow snout. Also, while coloration is not necessarily a good identifying feature, adult alligators are generally dark grey or blackish.

American alligator, Busch Gardens Florida;

(Photo by rustyallie)

Chinese alligator, Tennōji Zoo;

(Photo by muzina_shanghai)

Instead, the photos depict a false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii), an endangered species of crocodilian native to freshwater habitats in Southeast Asia.

False gharial, Singapore Crocodile Farm;

The false gharial is one of the larger extant crocodilian species, with really large individuals capable of reaching lengths of 5 or even 6 metres;

The longest skull in this photo is actually that of a huge false gharial; at 84 centimetres long, it happens to be the longest known modern crocodilian skull in existence, at 84 centimetres. Unfortunately, we do not know the total length of this giant. The skull of a more 'normal'-sized false gharial is seen at the bottom of the row;

(Photo from Tetrapod Zoology)

The same skull of a giant false gharial, with scientist Colin McHenry for scale;

(Photo by George Craig, posted on Here Be Dragons)

Unlike the estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), which is often encountered in coastal areas and even enters fully marine habitats, the false gharial is a freshwater specialist, preferring the slow-moving, heavily vegetated, often acidic waters associated with peat swamps and freshwater swamp forests.

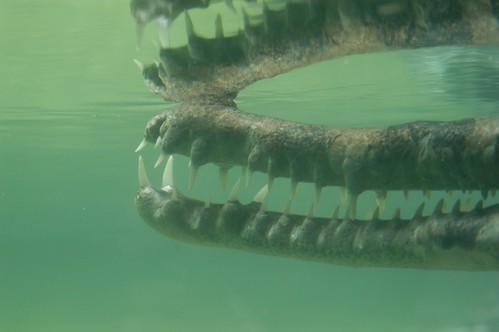

The false gharial's long, narrow snout is thought to be an adaptation to a diet consisting mostly of fish, allowing it to quickly sweep its jaws through the water, snapping up fish with comparatively little water resistance. In this case, the false gharial has sacrificed strength for speed; its jaws are weaker and not so well adapted to say, crushing the hard shells of turtles (something the American alligator does very well), or grabbing and holding on to large struggling prey (like the estuarine crocodile).

Head of false gharial, Singapore Crocodile Farm;

However, contrary to what is often stated in the literature, the false gharial is not necessarily limited to a diet of fish and small vertebrates alone; large adults are capable of taking larger prey such as monkeys. Occasionally, as was first documented in Kalimantan in 2008, very large false gharials will even prey on humans.

Head of false gharial, Singapore Crocodile Farm;

Compared to other crocodilians, little is known about the false gharial in the wild. A recent study indicates that this species has declined or even vanished from many areas it once inhabited, largely due to habitat loss; clearing of swamp forests for agriculture, fossil fuel extraction or settlements is seen as 1 of the biggest threats to the survival of false gharial populations, as it is not exploited for leather like other crocodilians. The current distribution has become highly fragmented, increasingly restricted to shrinking islands of suitable habitat. Borneo is seen as the stronghold for the species, and numbers have diminished in many parts of Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra.

Confusing Kinship

Drawing showing differences in head and snout shape between gharial (top), crocodile (middle), alligator (bottom);

(Drawing taken from Adam Britton)

The false gharial's appearance is reminiscent of another species of crocodilian, the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) of the Indian subcontinent.

Gharial, San Diego Zoo;

(Photo by mliu92)

Despite the similarities, it was believed that the false gharial and gharial were only distantly related; in the crocodilian family tree, the 3 extant crocodilian lineages arose in the Late Cretaceous period. The gharial lineage (Gavialoidea) split off first, followed by the divergence of the alligators and caimans (Alligatoroidea) and crocodiles (Crocodyloidea), with the false gharial being a crocodile whose similarities to the gharial were merely superficial. Based on anatomical characters alone, the false gharial seems more closely related to the crocodiles, and so it was interpreted as a case of convergent evolution, having independently evolved long, narrow jaws like those of the gharial.

Gharial (below) and false gharial (above);

(Painting by Carl Buell)

This was contradicted by the advent of molecular analysis, which enabled one to look beyond physical features. It was revealed that in terms of biochemistry, the false gharial and gharial actually appear to be each other's closest relatives after all, and in turn they are more closely related to crocodiles, with the alligators being more distant relatives. However, this is still far from resolved, and many classification schemes still include the false gharial as a member of the crocodile family. This review provides a summary of the complex history of extant crocodilians, and the mysterious affinities of the false gharial are discussed further.

Crocodilian cladogram, showing the conflict between molecular and morphological data with regards to phylogeny and divergence timing;

(Diagram from Christopher Brochu)

False gharial in Singapore?

It is unknown whether the false gharial was ever native to Singapore; it is listed in A First Look at Biodiversity in Singapore and A Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Singapore, but is not mentioned in the more recent Wild Animals of Singapore.

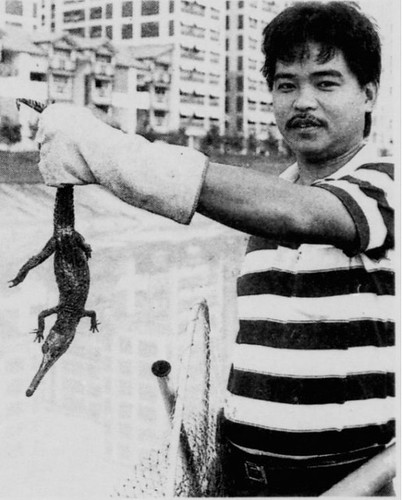

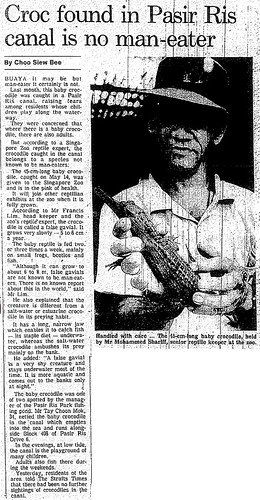

However, there is an extremely intriguing record of a young false gharial (approximately 50 centimetres long) that was captured in Sungei Tampines in Pasir Ris in May 1991, which might account for it being listed in the older publications. What makes this so interesting is that this seems to be the only recent record of false gharial in Singapore. Also, the canal flows through urban neighbourhoods and is under tidal influence, an environment which is very different from the peat swamp forests where false gharials are typically found.

The Straits Times, 15th May 1991; (Click on image to enlarge)

If only we had more clues that could reveal the provenance of this false gharial. Did Sungei Tampines have a breeding population of false gharial? Or did this young false gharial swim over from Johor (where false gharial have not been recorded)?

The Straits Times, 6th June 1991; (Click on image to enlarge)

In either scenario, does this mean that false gharial will venture into river estuaries and marine environments? Despite being restricted to freshwater habitats, the false gharial possesses salt-excreting glands similar to those found in the estuarine crocodile, hinting that it might be able to tolerate saltwater to some degree. Also, fossils of many of the false gharial's prehistoric relatives have been discovered in deposits laid down in coastal environments. This suggests that the false gharial's ancestors and other extinct kin (collectively known as the tomistomines) first evolved and adapted to marine habitats.

Skull of Gavialosuchus americanus, an extinct tomistomine from marine deposits in Florida, dating back to the late Miocene and early Pliocene epochs;

(Photo by Esv)

Another possibility, which I personally find the most plausible, is that this was a former captive that had been released or abandoned. People with pet crocodilians are actually not uncommon, and it is plausible that someone might have been keeping a baby false gharial as a pet, only to set it free in the canal when it started getting a bit too large. Sad to say, many pet reptiles meet such a fate when their irresponsible owners lose interest or find themselves unable to cope with a large, potentially dangerous reptile.

One last point of interest is that this young false gharial was apparently not alone; the reports state that 2 crocodiles were spotted, and the smaller one was caught. Details about the larger crocodilian, such as its size, or whether it was also a false gharial, are all unknown. In any case, it was never seen again.

As an aside, in 2008, a young estuarine crocodile was seen and subsequently captured, also in Sungei Tampines.

Besides this particular record, however, it seems that at least in recent years, the only crocodilian species present in Singapore is the estuarine crocodile.

Captive false gharials

As far as I know, the only false gharials in Singapore are all captives; when I visited the Singapore Crocodile Farm a few years back, it had an enclosure with several false gharials.

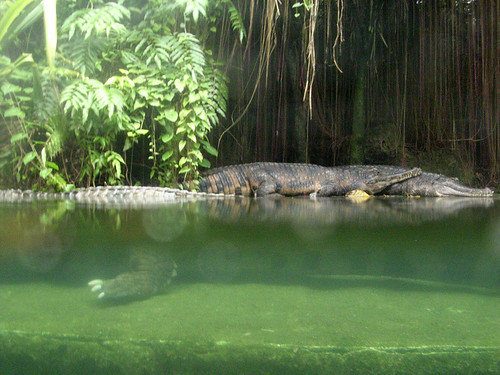

Enclosure with false gharials, Singapore Crocodile Farm;

However, the best place to find false gharials in Singapore is the Singapore Zoo, which has 3 different exhibits featuring false gharials:

The Bornean Marsh;

(Photo by Abhishek Roy@Singy)

(Photo by Preethi13)

(Photo by blinktwice4y)

(Photo by aladin2002in)

Sungei Buaya;

(Photo by El Duderhino

(Photo by The Occasional Mumble)

(Photo by pixxiefish)

(Photo by absolutmocha)

and the Treetops Trails;

(Photo by dadaabab)

(Photo by eyesthruthelens)

(Photo by iamthemessiah)

(Photo by AkumAPRIME)

(Photo by Ling-Hann Kim)

(Photo by Amsk)

(Photo by Shahzeb Nasir)

Exposing the Truth

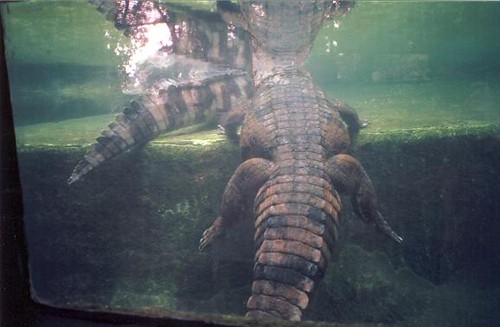

What I found most interesting is that in the photos allegedly documenting a false gharial in Sembawang Park, the bank that the reptile is resting on looks very odd. It certainly does not look like a natural riverbank or shore of a lake, especially with the unnaturally straight edge and what looks like a sudden drop in water depth instead of a gradual slope.

I have never been to Sembawang Park, but based on the map I downloaded from the NParks website, I do not see any ponds, rivers or other water bodies for an adult false gharial to live in. And even if we take into account the unlikelihood of a false gharial being spotted along the coast, I am sure the beach at Sembawang Park looks nothing like that shown in the photos.

Instead, the photos posted on STOMP remind me of an exhibit at the Singapore Zoo. Here are more pictures of the false gharials in the Treetop Trails exhibit:

(Photo by PurpleUnicorn)

(Photo by Amsk)

(Photo by msbell)

(Photo by MattFM)

(Photo by lkarzag)

I'm convinced that it is all a bad hoax, that the person used photos of a false gharial at the Singapore Zoo to claim that an alligator was seen at Sembawang Park.

To verify this, I posted on the wall of the Facebook page of Wildlife Reserves Singapore, and received a reply:

So that seals it: this submission was nothing but a poorly-disguised hoax. I'm annoyed not just at the person who submitted the information, but also at the people running the STOMP website. I understand that they might receive an overwhelming number of daily submissions, but I wish that they wouldn't post submissions verbatim without basic fact-checking and verification from reliable sources.

This STOMP post fails on 2 levels; there's misidentifying a false gharial and calling it an alligator. Then there's the lying about the location, and the risk of possibly causing unnecessary panic and a waste of resources should the authorities be activated to catch a large crocodilian that doesn't exist in Sembawang Park in the first place.

Such blatant false reporting calls into question the integrity of such so-called "citizen journalism". Why be truthful when one can fabricate a report which will be published without any fact-checking beforehand?

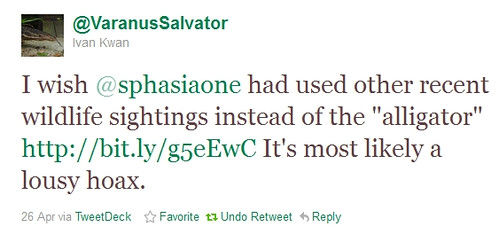

Postscript: Singapore Press Holdings, which owns STOMP, made yet another gaffe. AsiaOne Multimedia (which is also owned by SPH) did a short online article on recent wildlife sightings in Singapore, and mentioned the "alligator" at "Sembawang Park", while overlooking several other legitimate records of native fauna in urban Singapore.

I tweeted about my displeasure with the article:

To their credit, AsiaOne edited the article (but without explicitly calling it a hoax), and added in a few more genuine local wildlife sightings. But in their attempt to make up for their initial lack of fact-checking, they made yet another error:

An alert reader, tweeted that what looked like an alligator, was actually a false gharial. Pictures of the critter were sent into STOMP and posted yesterday by the citizen journalism website. The reader who sent in the pictures claimed that they were taken at Sembawang Park.The new mistake here is confusing the Treetops Trails exhibit at the Singapore Zoo with the Tree Top Walk at the Central Catchment Area.

However, a later Facebook post by the Singapore Zoo verified that the picture was likely to have been snapped at the Treetops Trail, a nature trail that is accessible from MacRitchie Reservoir.

I tweeted again, hoping that AsiaOne would make the necessary edits, but up until now, nothing has been changed.

I wish our mainstream media could aspire to be more accurate and discerning about the material that is often submitted, especially to STOMP. While STOMP can be a useful resource for wildlife sightings, it can be disappointing to see it being used as a repository for biased reporting, urban legends, and hoaxes.