STOMPer Vincher was shocked when she came across the carcass of this headless bird in a Clementi carpark.

"Was it murdered by a cat?" she wondered.

"I found this poor headless birdie in front of block 702 Clementi at carpark c35 in lot 604.

"I really felt sorry for the bird. I spotted it at 8:30am today (Apr 8)."

There's a couple of possibilities:

The first possibility is that this feral pigeon (Columba livia) was killed by a cat, which bit off the head. However, the lack of any signs of a struggle, such as blood and loose feathers scattered everywhere, make this quite an unlikely explanation.

The second more plausible option is that the head is merely tucked beneath the bird's body, such that it is obscured from view.

Beneath all their feathers, birds actually have long necks that are capable of some degree of flexibility. You would be surprised at how thin the necks of some birds actually are, beneath all the feathers.

(Photo by Flint-Hill)

Naked neck, a breed of domestic chicken (Gallus gallus) that lacks feathers on its neck;

Even pigeons, which appear to have short stumpy necks, have surprisingly slender necks. This is easily seen in the Romanian naked neck tumbler, a fancy pigeon breed that lacks feathers on the neck.

Romanian naked neck tumbler;

(Photo by jim.gifford)

Pigeon skeleton;

(Photo by Ryan Somma)

It is this flexibility that enables the bird to tuck its head away while sleeping or resting, and appear headless. I would suppose that in the case of this pigeon, moving the carcass would reveal the head.

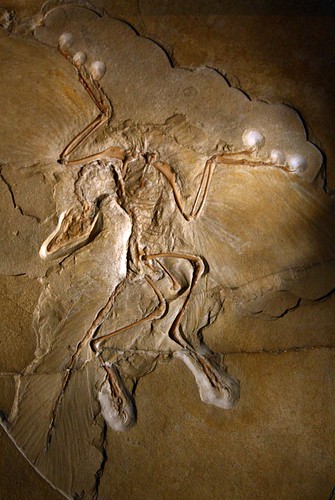

It is interesting to note that such flexibility is also seen in non-avian dinosaurs, especially in theropods, which birds are descended from. Quite a few skeletons of dinosaurs are recovered with the head thrown back over the shoulders, in a death pose that is seen in many specimens.

Gorgosaurus libratus, Royal Tyrell Museum;

(Photo by Royal Tyrrell Museum)

Struthiomimus altus, American Museum of Natural History;

(Photo by Nilesh Karia)

Compsognathus longipes, Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences;

(Photo by tina_manthorpe)

Archaeopteryx lithographica, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin;

(Photo by Hornplayer)

It was originally hypothesised in 1918 by Roy Moodie that these dinosaurs had died as a result of poisoning or disease, although it was eventually rejected by others in favour of theories that such poses were the result of water currents, or the shrinking and dessication of ligaments and tendons as the carcass decayed, pulling the neck back.

However, in 2007, Cynthia Faux and Kevin Padian published a paper claiming that such explanations were wrong, and that this pose was more likely to be caused by brain damage. Experiments showed that rigor mortis or shrinking of ligaments during decomposition failed to account for such poses. Instead, this pose, known as opisthotonus, is associated with damage to the cerebellum, which can occur as a result of suffocation, disease, brain trauma, or poisoning. Hence, instead of having taken place through postmortem processes, the opisthotonic posture indicates that violent death throes had taken place at the moment of death.

GrrlScientist of Living the Scientific Life (Scientist, Interrupted) and Bora Zivkovic of Coturnix have provided excellent summaries of this paper. While Brian Switek of Laelaps reminds us why this is not necessarily an open-and-shut case.

If such a posture is indeed suggestive of poisoning, it does raise a few questions as to how this particular pigeon died. Was it killed by poisoning? There has been quite a bit of a ruckus in recent months over the culling of pigeons; pigeons are culled with the use of poisons, which does raise quite a number of issues. I'm particularly concerned about the possibility of collateral damage when non-targeted species feed on poisoned baits, and the fact that culling is ineffective when not carried out in tandem with other control measures, such as reducing the availability of food for the pigeons in the first place.

Problems with urban birds are essentially human problems. In most cases, the most effective long-term solution involves changing human behaviour. Whether it is stopping people from feeding pigeons, enforcing proper food waste disposal, or prompt clearing up of leftovers at food outlets, such measures can go a long way towards preventing pigeon numbers from exploding. Culling is only treating the problem, not the source.

Fangqi has taken up this issue, and now compiles all relevant articles and letters on pigeons on the Save The Pigeons blog.