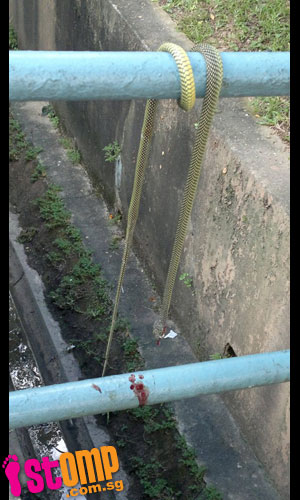

At first glance, it looked like a rope wound around a railing. However, STOMPer Christina soon found out it was a dead snake.

Recently, snakes have also been spotted on Upper Thomson Road and in a drain at Bukit Panjang. These reptiles could have been seeking refuge from the recent heavy downpour.

Christine wrote in her contribution (June 8):

"Dead snake found along Henderson Road!

"An unknown dead snake was found along Henderson Road at the Block 113 drain on 8th June 2011!

"The snake was found dripping blood from its mouth when it was discovered.

"It is unclear how the snake came to be hanging dead in the HDB district."

I always get a little upset whenever I see posts on STOMP about wildlife being unnecessarily harassed or even killed. It was, after all, an old post several years back about someone who killed a harmless snake in his flat that made me register on the site to comment, to rebut those comments applauding the act of eliminating a dangerous animal.

The (sadly deceased) snake in this post is a paradise tree snake (Chrysopelea paradisi), a species that is commonly seen in many parts of Singapore, from forests and mangroves to urban parks and gardens.

Sungei Buloh;

(Photo by Marcus)

This is an arboreal snake that spends most of its time off the ground, and seems to favour hiding in the crowns of palm trees. My very first encounter with this species, as an undergraduate in NUS, was when a pest control company was called in to catch a snake that had been seen in a small palm tree along a corridor in the Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences. A large crowd had gathered, and given the commotion, I was wondering if it was a python. When I finally caught a glimpse of the snake as it was removed from the tree and bagged, I was disappointed that it was 'just' a paradise tree snake.

Subsequently, I had friends who saw this species elsewhere in the faculty; some of them saw a snake eating a changeable lizard (Calotes versicolor) at the Arts Canteen, while another managed to take photos of a paradise tree snake in a corridor close to where the Department of South Asian Studies was located.

Paradise tree snake spotted in FASS corridor, NUS;

(Photos by Jasmine Lee)

Another photo of a paradise tree snake, taken close to the Arts Canteen;

(Photo by Daryl Seah)

A close encounter I had with this species was at Sungei Buloh in 2008; a snake was slithering on the boardwalk railings in my direction; when it saw me, it ducked and hid between the planks.

A more recent sighting was during my In-Camp Training this year, during an outfield exercise somewhere in the Western Catchment Area. I happened to be scanning my surroundings when I saw a large paradise tree snake on a tree trunk. When I approached it, the snake promptly climbed higher into the branches and vanished. Needless to say, I was not able to take any photos.

A few months ago, a Twitter acquaintance of mine was on Pulau Ubin, when he also had an encounter with a paradise tree snake. After he took a photo, the snake apparently glided through the air and disappeared into the forest. "Glided through the air?", you may ask incredulously. Indeed, the paradise tree snake is a snake that actually glides, and is also known as the flying snake. More on that later.

The paradise tree snake has a wide distribution across Southeast Asia, from the Andaman Islands in the west to the Philippines and Sulawesi in the east. It is also present in southern Thailand and Myanmar, Malaysia, Brunei, and much of Indonesia.

(Photo by Marcus)

The paradise tree snake is diurnal, which means that it is most active during the day. It has large eyes and excellent eyesight, and has been observed to watch and track the movements of birds flying overhead, probably keeping an eye out for potential predators. A closely related species, the golden tree snake (Chrysopelea ornata), has also been observed to react the same way to aeroplanes.

(Photo by kwokwai76)

(Photo by *Damselfly*)

Growing to around 1 metre in length, paradise tree snakes have this beautiful black and green speckled coloration, which also makes them instantly recognisable.

(Photo by hiker1974)

Many individuals also display a beautiful red pattern.

The paradise tree snake is a rear-fanged snake; it has very small fangs at the back of its mouth. It's not as refined as the venom delivery system of say, a cobra or viper. In rear-fanged snakes, the fangs don't act like hypodermic needles to inject venom into the prey. Instead, the venom flows down grooves on the surfacee of the fangs and into the wound. Which is why rear-fanged snakes in general are often seen hanging on to their prey and making 'chewing' motions, so as to deliver more venom.

In any case, the venom of the paradise tree snake is not considered dangerous to humans, but it allows the snake to subdue its usual prey, consisting mainly of lizards and frogs. After venom is injected, the snake coils around its prey, probably to hold it in place while the venom takes effect, and also to constrict and suffocate the victim so as to kill it more quickly.

Paradise tree snake swallowing spotted house gecko (Gekko monarchus), Forest Research Institute Malaysia;

(Photo by leopardcat)

Paradise tree snake swallowing tokay gecko (Gekko gecko), Langkawi;

(Photo by Rich_Ella)

Larger individuals will also attack small birds and bats.

Paradise tree snake attempting to feed on young bat;

(Photos by hiker1974)

This bat eventually proved to be too much of a mouthful for the snake. Yes, despite being able to swallow prey far larger than expected, snakes do still have their limits.

This video documents an attempt by a paradise tree snake to swallow a bat wedged inside a slit in a bamboo stem, either a greater bamboo bat (Tylonycteris robustula) or lesser bamboo bat (Tylonycteris pachypus). Although the snake appears to have been successful at killing the bat, it was not able to remove the bat from its hiding place and eventually had to give up.

Flying snakes?

The paradise tree snake and its relatives are often known as flying snakes, because of their remarkable and unique ability to glide. These snakes will actually launch themselves into the air, and control their descent to some degree, enabling them to travel a considerable distance while airborne.

Flying snakes are amazing, but it is even more intriguing that the forests of tropical Asia are home to such a diverse range of gliding creatures, compared to forests in South America and Africa. Besides 5 species of flying snake (Chrysopelea spp.), there are also several species of flying squirrels (F. Sciuridae), colugo or flying lemurs (F. Cynocephalidae), flying frogs (F. Rhacophoridae), gliding lizards (Draco spp.) and gliding geckos (Ptychozoon spp.). The reasons behind such an amazing diversity of gliders in the region are are still not well known. Certainly, falling is an inevitable part of life for arboreal animals, and many species of squirrel, frog, lizard and snake not thought of as gliders are able to spread out their bodies and parachute, slowing their fall to reduce the risk of serious injury when landing. The various gliding species are unique in how they are able to use this as a way to travel not just vertically, but horizontally as well.

Unlike other gliding animals, which rely on extending flaps of skin or membranes, the paradise tree snake uses its entire body as a "wing" to keep it aloft. A snake that is ready to glide will crawl out to the end of a branch and hang from it, with the front part of the body forming a J-shaped loop, leaning forwards and upwards to adjust the angle of its flight trajectory, as well as to select a desired landing spot. Then, the snake pushes off with its tail while straightening its body, and literally leaps off.

While gliding, a paradise tree snake spreads out and flattens its ribs, turning it from a cylindrical tube into a ribbon with a concave bottom. Resembling a frisbee in cross-section, this shape helps generate lift to slow its rate of descent. At the same time, the snake holds its body in an S-shaped configuration while undulating its body from side to side, appearing as if it is swimming through the air. This is also thought to help keep the snake airborne. In this way, the flying snake is able to travel up to 100 metres before it loses speed and lands, preferably in a tree. It is even able to turn and change direction in mid-air!

One would think that a snake, without any appendages or gliding membranes, would not be a very good glider, but it turns out that the paradise tree snake is a superb glider that has a good gliding ratio (the ratio of horizontal distance gained to height lost), on par with flying squirrels and gliding lizards.

It is possible that gliding is a way to reduce the amount of energy spent travelling from tree to tree; flying snakes can avoid descending to the ground and risk attack from terrestrial predators, and save time and energy that other snakes have to use in climbing up and down trees. Gliding is also a possible way to escape arboreal predators, as well as a possible means to chase prey in another tree.

The flying snakes' secret of gliding has been extensively researched by biologist Jake Socha, who studied paradise tree snakes in Singapore in 1997 and 2000. He set up a website dedicated to these snakes, and has published extensively on their gliding abilities. The videos he has recorded of flying snakes taking off and gliding are very interesting indeed.

His work on flying snakes has been the subject of at least 2 National Geographic documentary programmes, and has also been mentioned in many news articles.

How dangerous?

Based on my sightings, as well as those by others, it appears that the paradise tree snake is generally more likely to flee rather than stand its ground. However, some comments posted on discussion forums for owners of exotic reptiles do suggest that this snake will turn aggressive and readily bites if handled.

As far as I know, I have never heard of any local cases of people being killed or hospitalised by the bite of a paradise tree snake. Local naturalist R. Subaraj lists the paradise tree snake as one of three species of mildly venomous snake that have bitten him many times before, but with no ill effects. Jake Socha himself mentioned that he had "been bitten many times with no effect." So it does seem that the snake is pretty much harmless to people; sure, the reaction to a bite may vary from person to person, but it seems that for most people, bites by a paradise tree snake don't cause any significant medical issues.

Like I usually tell people who ask whether a particular spider or snake is venomous, "Yes, it's venomous, but it won't kill you. You might feel lousy for a while, but you'll survive."

Cousins

The paradise tree snake has a relative in Singapore, the twin-barred tree snake (Chrysopelia pelias).

(Photo by NatureInYourBackyard)

Somewhat smaller than the paradise tree snake, this species is considered rare, being restricted to forest habitats. It too is found in Southeast Asia, from southern Thailand and Peninsular Malaysia to Sumatra, Borneo and Java.

(Photo by hiker1974)

I personally think that its coloration is even prettier than that of its relative. The twin-barred tree snake preys largely on lizards, and a 2009 paper reports on an overly ambitious individual that tried to swallow a gecko that was too large for it.

(Photo by mamuin)

Interestingly enough, there is a paper from last year describing the effects of a bite by a twin-barred tree snake in Malaysia. The initial symptoms included feeling faint, a headache and mild giddiness, and numbness and moderate pain in the affected foot, which travelled up the thigh. This was followed by a borderline fever, and while the numbness subsided, the pain still lingered. Blood and urine tests revealed slightly higher than usual levels of haemoglobin in the urine, as well as slightly elevated production of white blood cells and subsequently, platelets. The slight pain persisted for a few more days, but besides that, there were no major medical problems.

I suppose this could be considered a somewhat more serious case of envenomation by a Chrysopelea snake, although one could say that the symptoms are very mild compared to bites by more venomous snakes. I guess a serious bite by a paradise tree snake would probably be quite similar in terms of symptoms and medical effects.

Another relative which is not found in Singapore is the golden tree snake. As I mentioned earlier on, snakes of this species have been recorded watching and tracking the movements of planes passing overhead, a testament to the good vision possessed by these snakes.

(Photo by Thai pix Wildlife photography)

This can be considered the northern counterpart of the paradise tree snake, being found in southern India and Sri Lanka, Indochina, Thailand, and northern Peninsular Malaysia. Similarly, it is adaptable and commonly seen in urban gardens within its range, but grows slightly larger, up to 1.3 metres in length.

(Photo by ╦hØm△₪)

(Photo by PJ Hudson)

Living with serpents

Being a common species, paradise tree snakes are often encountered by people in Singapore, and unfortunately, do bear some of the brunt of the ignorant paranoia that many people still have about snakes. My guess is that this particular snake was killed by a person, although one cannot discount the possibility that it was crawling along the railing when it became the unfortunate target of mobbing by birds such as mynas or crows, which attacked it so ferociously that the snake was mortally wounded.

The Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES) Wildlife Rescue team frequently relocates snakes that have wandered into residential areas all over Singapore; some individual paradise tree snakes that have been rescued bear nicknames like Jack Sparrow, Ruby, Chatreuse, Stapler, Kiddo, Dell Boy, Stripes and Streamer.

Considering that paradise tree snakes, like many of the other snake species we commonly encounter, are quite harmless and unlikely to attack unless cornered, it really is quite upsetting to see a snake treated in such a manner; in many rescue cases, it's more about protecting wildlife from the misguided fear and paranoia of people.

I feel that it is essential for people to at least learn to differentiate the harmless snakes from the more dangerous species, and to understand that there is no way we can ever completely stop snakes from living amongst us. Instead of the completely unnecessary persecution of all snakes, why not accept their presence, and appreciate their beauty?