Black and white ribbon worm (Baseodiscus delineatus), Terumbu Pempang Darat;

Red ribbon worm, Kusu Island;

(Photos by Ria)

Most ribbon worms live in marine environments, with a small proportion adapted to freshwater habitats. Just earlier today, I learnt that a small handful of nemertean species have actually managed to colonise the land, and that they can be found in Singapore!

For those of us who explore the forests at night, it's not uncommon to find arrowhead flatworms (F. Bipaliidae) with their characteristic heads, especially in damp areas, or after heavy rain.

Two species of arrowhead flatworm seen in Singapore's forests;

(Photos by James)

However, we've also seen a different sort of worm, one without the arrow-shaped head. There are no segments, so these are not annelid worms, like the leeches and earthworms. All this while, we've assumed that they were a different sort of terrestrial flatworm, though they weren't exactly very flat.

Chestnut Avenue, 5th February 2011;

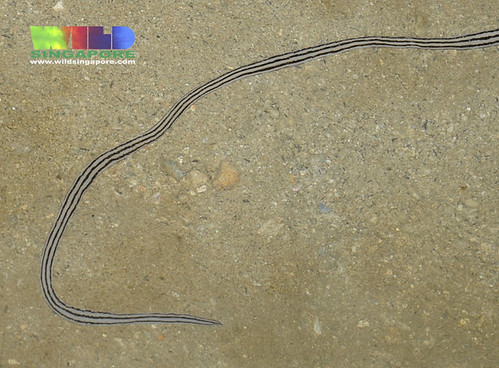

This type of worm is quite small, about 5 centimetres in length. Thin and slender, it has longitudinal stripes running down the length of its body.

Chestnut Avenue, 5th February 2011;

(Photos by Kok Sheng)

Dairy Farm Road, 14th July 2010;

(Photo by James)

James has found one of these worms entangled with an apparently dead jumping spider. Was the worm eating the spider?

Durian Loop, 17th December 2011;

Yesterday, Nicky shared this photo on Facebook, asking if anyone knew about the identity of this enigmatic worm. Here are more photos by Nicky, taken at the Durian Loop on 17th December.

While I still believed that it was a flatworm, Melvyn ventured that it might be a ribbon worm. I looked up the Wikipedia entry on ribbon worms, and found the following useful snippets of information:

Mainly in the tropics and subtropics, about 12 species appear in freshwater, and about a dozen species live on land in cool, damp places, for example under rotting logs.A search on Flickr for 'Geonemertes' revealed the following photos:

[...]

Another terrestrial genus, Geonemertes, is mostly found in Australasia but has species in the Seychelles, WIDELY ACROSS THE INDO-PACIFIC, in Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic, in Frankfurt, in the Canary Islands, in Madeira and in the Azores. (Emphasis mine)

Sabah, Borneo;

(Photo by artour_a)

Tangerang, Java;

(Photo by gbohne)

Fraser's Hill, Peninsular Malaysia;

(Photo by terraincognita96)

I also managed to find more photos of what seems to be feeding behaviour in terrestrial nemerteans.

(Photos by Kurt (orionmystery.blogspot.com))

Florida;

(Photo by smccann)

It seems increasingly likely that these are terrestrial ribbon worms. Which is amazing, because not too long ago, I'd only just learnt that there was a small number of ribbon worms that lived in freshwater.

One thing I noticed about the macro shots of these nemerteans is the presence of 2 small eyes, often making them look a lot like miniature blind snakes (F. Typhlopidae). You can clearly see the eyes in the following photos:

Left: Chestnut Avenue, 17th July 2010; (Photo by James)

Right: Chestnut Avenue, 5th February 2011; (Photo by Kok Sheng)

Not all nemertean species possess eyes, but in those that do, the number may vary, from 2 to 176 eyes! James has a photo of another unidentified worm, which intriguingly, appears to have multiple pairs of eyes.

Nangka Trail, 16th July 2011;

It is believed that the simple eyes are used primarily for detecting light; like all soft-bodied terrestrial animals prone to dessication, terrestrial nemerteans shun the light.

Terrestrial ribbon worms are not very well-studied at all, and although thirteen species have been described from around the world, it appears that there is no information about the nemerteans found in the forests of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. However, a handful of species are known to be very widely distributed. For example, a species known as Geonemertes pelaensis has apparently been found in places as far-flung as Mauritius, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Sulawesi, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Japan, Palau, Samoa, Hawaii, the West Indies, Bermuda, and Florida. If I had to hazard a guess as to the identity of our own terrestrial nemertean, this would be it.

Leptonemertes chalicophora was first discovered in the Palm House in Frankfurt, but has subsequently been found in California, Madeira, the Azores, and the Canary Islands. Another widely distributed terrestrial nemertean is Argonemertes dendyi, which was originally found in southwest Australia, but has since been recorded in the British Isles, California, the Azores, the Canary Islands, New Zealand, and Hawaii. Presumably, thanks to the international trade in live plants, these worms have been inadvertently transported all over the world while stowing away in potting substrate.

Like most of their marine relatives, terrestrial ribbon worms are thought to be predators, although the feeding ecology of most species remains unknown. Ribbon worms are notable for their proboscis, which is the primary organ used in capturing prey. This proboscis is a long hollow tube that is usually tucked away within a sheath that may stretch for nearly the entire body length.

(Drawing from Bumblebee.org)

When the ribbon worm detects prey, muscles in the sheath around the proboscis contract, causing it to turn inside out and shooting it out of the worm's body at high speed. For some, the proboscis is coated in a sticky, toxic secretion that ensnares prey. For others, there is a sharp barb at the tip of proboscis known as the stylet, which punctures the victim while injecting toxins and digestive secretions. Either way, prey is immobilised, and is then either swallowed whole, or the insides are partially digested before being sucked out by the worm.

(Drawing from Animal Diversity & Evolutionary Principles FA2011)

In this photo, a marine ribbon worm (Paranemertes peregrina) is using its proboscis to attempt to capture a much larger polychaete worm, San Juan Islands;

(Photo from A Snail's Odyssey)

Here are some photos of a terrestrial ribbon worm (possibly Argonemertes australiensis) that illustrate the amazing length of the proboscis.

Before:

And after:

And this is a video of this same worm, showing how quickly the proboscis is launched:

(Photos and video by Daniel O'Brien)

The video also presents how the proboscis is used as an escape mechanism in many terrestrial nemerteans. After shooting out its proboscis, the worm retracts it while the tip is still stuck to the ground. This pulls the entire worm's body forward and away from the threat.

Besides the fully terrestrial ribbon worms, there are other ribbon worms found living in transitional habitats. For instance, our mangroves are home to a ribbon worm (Prosadenoporus sp.), which can be found in mud lobster mounds and under the bark of rotten wood or tree trunks. Once classified under Pantinonemertes, (which has since been synonymised with Prosadenoporus), this species is considered locally endangered. The exact species of mangrove ribbon worm found in Singapore is unknown, but there are other semi-terrestrial relatives in the region, such as Prosadenoporus winsori in Australia, and Prosadenoporus fujianensis in China, both of which were found in mangrove habitats.

The supralittoral zone, or the high shore, is another habitat where one may find ribbon worms that have gained some independence from the sea. Here, there are nemerteans that spend most of their lives out of the water, hiding in crevices and beneath rocks, wherever there is moisture.

Lazarus Island, 20th February 2011;

(Photo by Marcus)

Looks like we can't automatically assume that every unsegmented worm we find on land is a flatworm. While the arrowhead flatworms are unmistakable, there are a number of species of terrestrial flatworm that possess rounded or pointed heads, which can lead to a lot of confusion.

For instance, the forests are also inhabited by yet another species of worm. It is much larger than the terrestrial nemertean, around 10 centimetres in length. It's thicker-bodied, and is black with a thin pale dorsal stripe.

Chestnut Avenue, 5th February 2011

Chestnut Avenue, 5th February 2011;

(Photos by Kok Sheng)

Chestnut Avenue, 17th July 2010;

(Photo by James)

Tanah Merah, 18th April 2011;

It has a pair of small eyes, just like a terrestrial nemertean.

Admiralty Park, 22nd July 2010;

(Photo by James)

While writing this post, I was going to suggest that this was a second species of terrestrial ribbon worm found in Singapore. However, I ended up stumbling upon the Wikipedia entry on a species of terrestrial flatworm known as the New Guinea flatworm (Platydemus manokwari).

(Photo by Shinji Sugiura, taken from Wikipedia)

So, the large black worm we find in the forests is not a ribbon worm, but a flatworm after all.

Unlike the arrowhead flatworms, the New Guinea flatworm belongs to a different family, the Rhynchodemidae. First found on the island of New Guinea (where else?), the native distribution of the New Guinea flatworm is unknown. This species has been inadvertently introduced to other areas in the Indo-Pacific, such as the Maldives, the Philippines, Queensland, Okinawa and the Bonin Islands in Japan, Hawaii, Palau, Vanuatu, Mariana Islands, and Hawaii. It looks like we can add Singapore to the list of places where it has become established.

The New Guinea flatworm is a voracious predator, and preys heavily on terrestrial snails. Hence, it is feared that the spread of this invasive species has contributed to the rapid decline or extinction of many endemic land snails found on these remote Pacific islands. Whether it will have the same impact on our native snail fauna remains to be seen.

New Guinea flatworms attacking earthworms, woodlice and snails;

(Photos from Sugiura, 2009)

In many ways, both flatworms and ribbon worms, despite not being closely related at all, share a lot in common. A large majority of flatworms and ribbon worms are carnivorous. Both groups are predominantly made up of marine species, many of which are brightly coloured, with a small number found in freshwater and on land. And finally, both the ribbon worms and flatworms have terrestrial representatives that have become established in areas far from their native range, thanks to international shipments of plants and soil.

Gibson, R. (1995) Nemertean genera and species of the world: an annotated checklist of original names and description citations, synonyms, current taxonomic status, habitats and recorded zoogeographic distribution. Journal of Natural History, 29(2): 271-562.

Gibson, R. & Moore, J. (2001) Further observations on the genus Geonemertes with a description of a new species from the Philippine Islands. Hydrobiologia, 365(1-3): 157-171.

Moore, J. (1985) The distribution and evolution of terrestrial nemertines. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 25(1): 15-21.

Moore, J. & Gibson, R. (1981) The Geonemertes problem (Nemertea). Journal of Zoology, 194(2): 175-201.

Moore, J. & Gibson, R. (1985) The evolution and comparative physiology of terrestrial and freshwater nemerteans. Biological Reviews, 60(2): 257-312.

Moore, J., Gibson, R. & Jones, H.D. (2001) Terrestrial nemerteans thirty years on. Hydrobiologia, 456(1-3): 1–6.