Many people are finally clued in to the awesomeness of mantis shrimps, thanks to a hilarious comic by The Oatmeal.

This has been cited as an excellent example of science communication, and is also a great opportunity to highlight that Singapore has mantis shrimps too!

Many articles and documentaries refer to THE mantis shrimp, often without highlighting that there are around FIVE HUNDRED different species of all shapes, sizes, and colours. It is the large (up to 18 centimetres long), colourful, and active species known as the peacock mantis shrimp (Odontodactylus scyllarus) that has become the unofficial public representative of the entire group.

Bali, Indonesia;

(Photo by Yiqun Ding)

Similan Islands, Thailand;

(Photo by le congre)

Sipadan, Malaysia;

(Photo by .starlight.)

Maldives;

(Photo by tofulollipop)

It seems like even one of the most venomous animals in the ocean is no match if the peacock mantis shrimp strikes first.

The peacock mantis shrimp is not known to occur in Singapore waters, but is widely distributed in the Indo-Pacific. I wouldn't be surprised if it does actually live on our reefs, just that our divers have yet to spot one.

A number of other species of mantis shrimp have been documented in a variety of marine environments in Singapore, on coral reef and rubble, seagrass beds, and sandflats.

Spearers vs. Smashers

Mantis shrimps (also known as stomatopods) fall into two categories: the spearers have claws that work just like those of a praying mantis. Prey is literally impaled by the barbs and spines of the raptorial appendages.

Raptorial claws of Squilla aculeata, Panama;

(Photo by Arthur Anker)

Lysiosquillina lisa brandishes its spears, Malaysia;

(Photo by Jason Isley)

Lysiosquilla scabricauda, Florida;

(Photo by mentalblock_DMD)

In Singapore, I'm aware of the presence of at least 3 species of mantis shrimp that fall under the 'spearer' functional type.

There's a large grey-coloured spearer that is usually seen on sandy shores, often among seagrasses. For now, it's tentatively identified as belonging to the genus Harpiosquilla.

Chek Jawa;

(Photo by Ria)

Changi;

(Photo by Ria)

Pulau Subar Laut (Sisters Islands);

(Photo by James)

Another species of spearer that lives in Singapore is known as the banded mantis shrimp, also called the zebra banded shrimp (Lysiosquillina maculata). This species is much more rarely seen, as it never seems to leave its burrow. Most sightings have involved dead individuals.

This dying banded mantis shrimp was found washed up at Changi;

(Photo by James)

Similarly, this one was found dead on Tanah Merah after an oil spill;

(Photo by Ria)

This live specimen was found on Cyrene Reef;

(Photo by Ria)

Growing up to 40 centimetres in length, this is the largest of all the mantis shrimps.

But most of the time, this is all you'll ever see. Dumaguete, Philippines;

(Photo by Karen Honeycutt)

Lembeh, Indonesia;

(Photo by colin.robson11)

(Photo by Roy Caldwell)

While it was still open, the Public Gallery of the Raffles Museum Biodiversity Museum had 2 species of spearers on exhibit, both recorded as having been collected off East Coast Beach.

Harpiosquilla harpax might correspond to the large spearer we see regularly. This specimen is huge; based on my (admittedly imperfect) memory, it measured about 20 centimetres in length.

Harpiosquilla harpax;

(Photo by Chan Tim-Yan, from SeaLifeBase)

It's possible that we have actually also encountered the smaller Miyakea nepa, just that we've been confusing it with Harpiosquilla. These crustaceans are usually so quick and skittish in the field that it is difficult to take clear photos when we spot them outside their burrows, and their fearsome reputation means that we're understandably reluctant to get too close to take a look at their morphology.

Miyakea nepa;

(Photo by Chan Tim-Yan, on SeaLifeBase)

(Photo from Tiger I, on lowyat.NET)

One of the distinguishing features of Miyakea nepa is that it has small eyes. Which does make me wonder about the identity of some of the spearers we've encountered, such as this one at Pasir Ris;

(Photo by Ria)

The raptorial appendages of a spearer (left) and a smasher (right);

(Image from Michael Bok)

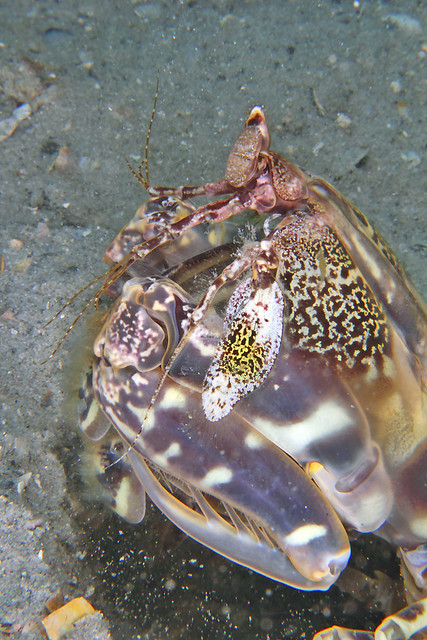

Unlike the spearers, the mantis shrimp classified as 'smashers' don't rely so much on the 'spear' (the tip of which is still sharp enough for stabbing), but rather, have the 'heel' expanded and hardened into a club. This is used to bludgeon hard-shelled prey, such as molluscs and armoured crustaceans like crabs. The most famous example of this functional type is of course the peacock mantis shrimp.

Thailand;

(Photo by prilfish)

![Odontodactylus latirostris (Pink Earred [Smashing] Mantis) - Dumaguete, Philippines](http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7167/6707166447_366e516911.jpg)

Odontodactylus latirostris, Philippines;

(Photo by Karen Honeycutt)

Gonodactylus platysoma, Australia;

(Photo by Michael Bok)

Hemisquilla californiensis, California;

(Photo by Michael Bok)

In Singapore, we sometimes see a small green smasher on our Southern shores, near reefs and seagrass habitats. This species has been identified as possibly being Gonodactylus chiragra.

Pulau Semakau;

(Photo by Ria)

Pulau Subar Laut (Sisters Islands);

(Photo by Chay Hoon)

However, the coloration of these shrimps does not match that seen in Gonodactylus chiragra from elsewhere.

Sulawesi, Indonesia;

(Photo by Scottish Exile)

Amami Islands, Japan;

(Photos by diver813)

Futuna Island;

(Photo by J. Poupin)

Could this be a case of misidentification?

The Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research Public Gallery had a small specimen of smasher collected from Sentosa, identified as Gonodactylellus viridis (the genus Gonodactylinus is now considered a synonym).

(Photo from Reeflex)

(Photos from AquaLifeImages)

Could this be the actual identity of the small green smasher we find on our shores?

Besides these 4 species, it's likely that there are more local species of mantis shrimps waiting to be found, especially in the museum's collections.

Anglers sometimes accidentally catch mantis shrimps, but it seems like these are almost always the large spearer (Harpiosquilla (?)harpax).

(Photos from Handlinefishing.com)

I did say that this particular species of mantis shrimp could get to very large sizes;

(Photo from Singapore Kelong)

Can eat one?

Yes, mantis shrimp is actually edible, and the larger species are actually caught and sold in many different parts of the world.

In Italy, mantis shrimp is known as canocchia, with the species Squilla mantis being harvested in large quantities.

Squilla mantis;

(Photo by Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, from SeaLifeBase)

(Photo by honeylotus)

(Photo by marlenekzio)

(Photo by the tαttσσed tentαcle)

In Japan, mantis shrimps are called shako (蝦蛄) and are either boiled and served as sushi topping, or eaten raw as sashimi. The most important mantis shrimp species in Japanese cuisine is Oratosquilla oratoria, although various Harpiosquilla species are likely to be targeted as well.

Oratosquilla oratoria;

(Photo by Chan Tim-Yan, from SeaLifeBase)

(Photo by head_syndicate)

(Photo by Mars Chen)

Mantis shrimp sashimi;

(Photo by orph3u5)

In Cantonese cuisine, mantis shrimps are known as 'pissing shrimp' (攋尿蝦: lai niu har) due to their tendency to shoot a jet of water when picked up. Deep-frying is a common method of cooking, although there are now other recipes and styles of preparation. Oratosquilla and Harpiosquilla are among the species harvested for Hong Kong markets.

(Photo by Kent Wang)

(Photo by crazybluepanda)

(Photo by Proxeman)

(Photo by alient76)

(Photo by joemorrison)

As a child, I don't ever remember seeing mantis shrimp in Singapore seafood restaurants; it seems to have been a recent introduction, maybe from Hong Kong or elsewhere in Southeast Asia, possibly partly due to its unusual appearance (at least, compared with the more familiar decapod crustaceans that we commonly eat).

Like in Hong Kong, the consumption of mantis shrimp in Southeast Asia appears to focus on various large species of Harpiosquilla, such as Harpiosquilla harpax and Harpiosquilla raphidea.

(Photo by Fred @ SG)

(Photo by Roberto Trm)

(Photo by ** David Chin **)

(Photo by onemorebiteblog)

Given that they are among the largest mantis shrimps, Lysiosquillina are also sought after, at least in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong seafood markets.

(Photo by mrbdxmpl)

(Photo by skasuga)

One interesting thing I've noticed is that Lysiosquillina are often displayed in plastic bottles.

(Photo by denn)

(Photo by Chung Ho Leung)

Presumably the mantis shrimp entered the bottle when it was young, then eventually grew too large to escape. Even in the wild, these burrowers would hardly ever leave their homes, so I'm not sure if this is necessarily cruel. My guess is that they were caught when young, then raised to market size while living in these artificial 'burrows'. But why is this done?

(Photo by bsmith4815)

Lysiosquillina is a spearer, so there's no way it's going to shatter a glass tank.

Is it to reduce the risk of injury to people sticking their hands in the tank? But then why are Harpiosquilla, which are also large and presumably potentially dangerous, not kept this way? Or does Lysiosquillina display strong antisocial and potentially cannibalistic tendencies? Images of groups of Lysiosquillina not confined to bottles seem to debunk that notion. Maybe they simply don't thrive if there's no 'burrow' for them to live in while they're being fattened up. It's really puzzling; let me know if you find out why this is done!

Potential for research

The Oatmeal covered some of the fascinating aspects of mantis shrimp biology: their amazing vision, sophisticated and deadly weaponry, and some of the possible applications. Sheila Patek's TED talk mentions some possible solutions to engineering problems that could be learned from mantis shrimps.

With powerful eyesight, it's not surprising that many mantis shrimp species are brightly coloured, and have evolved complex means of communication, often involving body posture, chemical and visual cues, and posturing and ritualised displays. When your rival or mate is armed with the same dangerous weapons that you yourself wield, communication is the key to avoiding excessive violence and unnecessary bloodshed.

There are numerous blog posts covering various discoveries of mantis shrimp biology; I highly recommend this compilation of posts by Ed Yong:

- Why are stabby mantis shrimps much slower than punchy ones?

- How mantis shrimps deliver armour-shattering punches without breaking their fists

- Mantis shrimp eyes outclass DVD players, inspire new technology

- The mantis shrimp has the world's fastest punch

- Mantis shrimps have a unique way of seeing

As well as this selection written by Michael Bok:

- I guess this means my study animal is mainstream now?

- Stomatopod Strike on CreatureCast

- Mantis Shrimp Bio-Armor

- How mantis shrimp see circularly polarized light

- Mantis Shrimp glow in the dark

- Mantis Shrimp Vision Preview

- Why Stomatopods are Awesome, I: Super Strength

To end this post, I highly recommend watching The Fastest Claw in the West (YouTube link), a 1985 Wildlife on One documentary that really started my own fascination with mantis shrimp.

(Photos by Jason Isley)