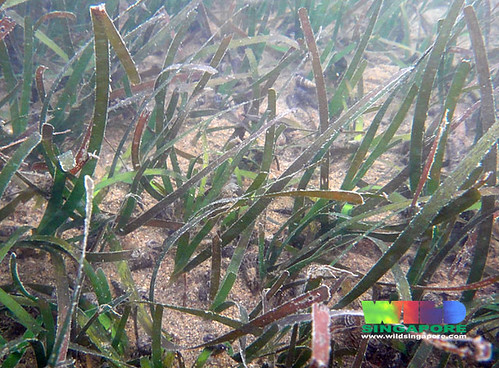

The leaves of various seagrass species found in Singapore;

(Photo by Ria Tan)

In the previous post, we took a look at seagrasses, some of the places in Singapore where you can find them, and also went through the ten species of seagrass recorded in Singapore in recent surveys. In this post, we'll find out why seagrass habitats are so important, and some of the threats they face.

Why are seagrasses important?

When it comes to threatened marine ecosystems, coral reefs get a lot of attention. Seagrasses, on the other hand, tend languish in obscurity.

With their roots and rhizomes (underground stems), seagrasses stabilise the soft sediments on the seabed, reducing erosion and allowing other marine organisms to settle.

Seagrasses are an important source of food for two large marine creatures.

(Photo by Francois Parot)

The dugong (Dugong dugon) feeds mostly on seagrass. It grazes by plucking a mouthful of seagrasses, shakes it to get rid of the sand and other sediments, and then swallows. Dugongs can eat up to 40 kilograms of seagrass every day!

(Photo by Rutger Geerling)

(Photo by Vanessa Costa)

Today, dugongs are very rarely seen in Singapore waters, but the feeding trails that they leave behind suggest that they often visit our seagrass meadows.

Dugong feeding trail at Chek Jawa;

Dugong feeding trail on Changi;

Another marine creature that feeds on seagrass is the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas).

(Photo by rinjani)

Not many other animals are able to digest seagrasses, but these plants still provide a vital habitat.

(Pulau Semakau)

(Chek Jawa)

(Chek Jawa)

(Tanah Merah)

(Cyrene Reef)

It's easy to see how these undersea 'forests' serve as a refuge for all sorts of marine life. Algae grows among or even on the seagrass blades, sustaining herbivores, which in turn are hunted by predators.

Orange striped hermit crab (Clibanarius infraspinatus);

(Changi)

Elbow crab (F. Parthenopidae);

(Changi)

Ornamented snapping shrimp (F. Alpheidae);

(Cyrene Reef)

Haddon's carpet anemone (Stichodactyla haddoni);

(Tanah Merah)

Knobbly sea star (Protoreaster nodosus);

(Cyrene Reef)

The seagrass meadows of Cyrene Reef are among the last places in Singapore where you can still find large populations of knobbly sea stars;

White sea urchin (Salmacis sphaeroides) and thorny sea cucumber (Colochirus quadrangularis);

(Changi)

Estuarine seahorse (Hippocampus kuda);

(Changi)

Alligator pipefish (Syngnathoides biaculeatus);

(Cyrene Reef)

Seagrass filefish (Acreichthys tomentosus);

(Cyrene Reef)

Cuttlefish (F. Sepiidae);

(Changi)

Noble volute (Cymbiola nobilis) pursuing a fleeing big brown clam (Mactra mera);

(Changi)

Dubious nerites (Clithon oualaniensis);

(East Coast Park)

The stabilised sediments found on seagrass meadows and the seagrass leaves themselves provide a sheltered places for various creatures to anchor themselves or to lay their eggs.

Egg ribbon of a nudibranch;

(Beting Bemban Besar)

Tiny sea anemone (awaiting identification) growing on seagrass leaf blade;

(Changi)

Many of the creatures that depend on seagrass habitats are species that we harvest for food.

Pearl conch (Laevistrombus turturella), also known locally as gong-gong;

(Tanah Merah)

(Cyrene Reef)

Banded prawn (Penaeus semisulcatus);

(Changi)

(Chek Jawa)

Blue-tailed prawn (Penaeus latisulcatus);

(Changi)

White-spotted rabbitfish (Siganus canaliculatus), also known locally as pei tor;

(Changi)

Mullets (F. Mugilidae);

(Chek Jawa)

Seagrass meadows are vital as nurseries for a wide range of species. Here juveniles can hide until they grow large enough to survive in deeper, more open waters. Productive fisheries are often linked to healthy seagrass beds.

Flower crab (Portunus pelagicus);

(Changi)

(Chek Jawa)

Young barracuda (Sphyraena sp.);

(Tanah Merah)

Young squaretail mullet (Ellochelon vaigiensis);

(Tanah Merah)

Tiny filefish (F. Monacanthidae);

(Changi)

Young white-spotted rabbitfish;

(Changi)

School of juvenile fishes;

(Berlayer Creek)

Seagrasses are even beneficial for coral reefs. By stabilising the seabed with their roots and rhizomes, and with their leaves slowing down the flow of water, allowing detritus to settle, seagrass meadows reduce sediment load, resulting in clearer water that benefits corals. In some coastal areas, seagrass meadows filter out and trap nutrients, sediments, and chemicals from the land, preventing them from affecting coral reefs further offshore. And by absorbing carbon dioxide, seagrasses can slightly reduce the acidity of the water, to the benefit of adjacent reefs.

Seagrasses and corals;

(Beting Bemban Besar)

Over time, as sediment accumulates on the seagrass beds, this deposited material can become stable enough to support the growth of mangroves.

Seagrasses growing next to mangroves;

(Pulau Semakau)

And in an era where climate change is the catchphrase, and the value of our wild places is often framed in terms of the ability to absorb carbon dioxide, seagrasses stand out as especially important in carbon sequestration. In a paper that was published in Nature Geoscience last year, it was calculated that seagrass meadows could store up to twice as much carbon as the world's forests.

This study estimated that seagrass captures a staggering 27.4 million tonnes of carbon each year, burying it in the soil below. And unlike forests that hold carbon for about 60 years then release it again, seagrass ecosystems have been capturing and storing carbon since the last ice age. That means that up to 19.9 billion tonnes of carbon are currently stored within seagrass plants and the top metre of soil beneath them – more than twice the Earth's global emissions from fossil fuels in 2010.

And despite covering only less than 0.2 percent of the world's oceans, they are responsible for more than 10 percent of all carbon buried annually in the sea. The potential for marine and coastal ecosystems in offsetting carbon emissions is increasingly being recognised, and is now often referred to as 'Blue Carbon'.

It does make you wonder how much of the carbon emissions from the industries at nearby Jurong Island, Pulau Bukom, and Pasir Panjang are being locked up by the seagrass meadows of Cyrene Reef;

In a famous paper from 1997 on the value of ecosystem services and natural capital, if one put a price on all the different functions and services of the world's ecosystems, such as nutrient cycling, absorption of carbon dioxide and release of oxygen, erosion control and sediment retention, production of food and raw materials, and so on, seagrass habitats would be worth US$19,004 per hectare every year, much more than coral reefs and tropical rainforests!

Why are seagrasses in trouble?

Despite their importance, seagrass habitats in Singapore as well as elsewhere are under threat due to many reason. In 2009, a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences calculated that the world has lost more than a quarter of its seagrass meadows, and the rate of that decline has grown from less than 1% per year before 1940 to 7% per year since 1990.

As usual, the big problem is development of coastal areas. Many seagrass patches have been buried or cleared due to land reclamation and other development projects.

For instance, some of Sentosa's seagrass meadows were lost due to reclamation for Resorts World Sentosa;

Because our waters are so murky due to sedimentation from land reclamation, shipping, and dredging, the amount of sunlight that our seagrasses can receive is limited. Any increase in turbidity might make it even more challenging for seagrasses to survive.

(Tanah Merah)

Pollution can affect seagrasses in several ways.

Oily sheen over seagrass in Tanah Merah after an oil spill took place off Changi East in 2010;

Litter and other debris on the shore can uproot and destroy seagrass beds when moved about by wave action;

(Tanah Merah)

(Labrador)

In Australia, severe flooding in recent years has led to unusually large amounts of sediments being washed into the sea, resulting in the loss of seagrass meadows due to burial as well as reduction in water clarity. There are fears that this will have an adverse effect on local populations of dugongs and green turtles.

Sediment plume at the mouth of the Burdekin River, Queensland;

(Photo by Kadek Indah)

Here, extremely heavy rains during the monsoons can lead to flooding in Johor, which results in sediments and freshwater pouring out of the mouth of the Johor River. This has resulted in mass deaths of marine animals at Chek Jawa in the past, although it's not known if seagrasses were affected. In any case, some seagrass species are more sensitive to low salinity, and may be killed off by flooding.

Flooding and runoff from farmland can also wash fertilisers and excess nutrients into the sea, resulting in algae blooms that make the water murkier, compete with seagrasses for light and nutrients, and simply overwhelm them.

Boat propellers in shallow waters uproot and rip up seagrass beds, and recovery can be slow. These are propeller scars in a seagrass meadow in Belize;

(Photo by John F. Bruno)

We sometimes encounter what appear to be 'bleached' seagrasses, in which the chlorophyll in the leaves has disappeared. Like coral bleaching, this phenomenon might be linked to environmental triggers, such as pollution, or elevated temperatures.

These were seen on Chek Jawa after an oil spill took place off Changi East;

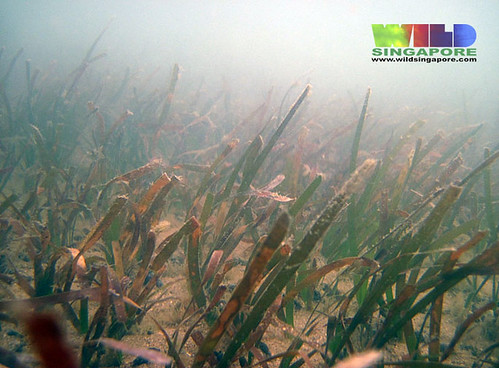

The state of tape seagrasses on some shores might also be linked to high temperatures.

Tape seagrasses once grew long and luxuriant on Cyrene Reef;

In the last few years, however, these seagrasses have been cropped short, with blackened tips that almost look as if they had been burnt. Has there been a change in the environment here that made it too warm for the tape seagrasses to grow properly?

In the final part of my post, find out what people are doing to help seagrasses in Singapore.

(All photos by Ria Tan unless otherwise stated)

(Cross-posted to SBA Plus. Do support me in the Singapore Blog Awards!)