(Photo by John 3000)

About a week ago, someone named Paul Chan wrote in to the Straits Times Forum, in response to reports of several long-tailed macaques attacking visitors to the Forest Walk along the Southern Ridges.

Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis);

(Photo by gamebit)

(The photos in this post feature several macaques that have been encountered by visitors to various parts of the Southern Ridges over the past few years)

Cull monkeys if over-population is the problem (Mirror)

I WAS shocked to read that a search was on for a monkey believed to have attacked three people over the past three weeks ("Attacks spark hunt for monkey"; last Friday).

I was also disappointed with the response of National Parks Board (NParks) officials that the monkey-feeding problem might have reached a tipping point and that sometimes, animals just go crazy. Did NParks do an extensive survey or study to arrive at such conclusions?

Despite many reports of rogue monkeys attacking people and foraging for food at bus stops and households, NParks prefers to pin the blame on human feeding or provocation.

The attack on Hort Park visitor Tang Mae Lynn was apparently due to the monkey pack invading her personal space at the Forest Walk; she carried no food or drink. The problem could be due to monkey over-population or lack of monitoring by NParks officials.

I disagree with NParks about not going after the monkeys because the creatures belong there as much as humans. Does that mean we should silently accept monkey attacks as normal?

It is the job of NParks to ensure monkeys behave where they co-exist with us. NParks has a duty to patrol and monitor the growth of the animal population within the forest boundaries. The animals should be culled if they encroach on human living space and disturb our peace. They should also be punished if they misbehave.

NParks could install closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras along the Forest Walk and areas prone to monkey attacks to check on the culprits while initiating programmes to control such disturbances so that both animals and people can share the limited space on our island in peace.

Paul Chan

(Photo by vlazygirl)

While we're at it, how about accusing the macaques of exhibitionist tendencies and sexual harassment? Where are their moral values?

There were so many flawed arguments in Paul Chan's letter that I frankly didn't quite know where to begin. My initial reactions after reading this letter are best illustrated using some rather famous Internet memes.

What is this I don't even

U MAD?

Are You Serious Face

Are You Fucking Kidding Me?

Rage Guy

It took me a while to compose my thoughts, and I drafted a reply, which to my satisfaction, was published today.

(Photo by amos1766)

Because of word limits, I had to omit a lot of points from the initial version I sent in to the Straits Times, and it underwent further edits before being published. Imposing word limits on a letter that's only meant to be published online seems silly, but we shan't go into that.

(Photo by spiderman (Frank))

In any case, here's the original reply I wrote.

People's behaviour at the crux of monkey problem

I refer to Paul Chan’s letter on Monday ("Cull monkeys if over-population is the problem").

Mr. Chan called for greater control of monkeys in our parks and nature areas, with culling as a measure if these primates encroach on our living space and disturb our peace, and as a punishment for any misbehaviour on their part. While I acknowledge that it is important for wild animals such as long-tailed macaques to keep their distance from people, I feel that the sentiments expressed by him fail to take into account the complexities of the issue.

Culling can be disruptive to highly social animals such as monkeys; removing high-ranking individuals can destabilise the social structure of the troop, and in the struggles that ensue as individuals compete and fight to fill the power vacuum, the cohesion of the troop breaks down. As smaller bands disperse or are driven out of the territory, they may inadvertently wander beyond park boundaries and into surrounding residential areas, where the risk of conflict arising between both primate species is greater.

Although I acknowledge that culling is often a necessary part of managing human-wildlife conflict, it should only be used as a last resort, if non-lethal means have been attempted and failed. The biggest flaw of culling is that it only gets rid of the symptoms temporarily; you can keep removing and killing the perpetrators of raids and attacks, but it does little to change the fact that many monkey individuals in some areas are becoming bolder. These are after all highly intelligent primates capable of developing their own cultural traits, and getting rid of one troublemaker does little to prevent others from imitating behaviour already seen as beneficial. In these cases, the monkeys have learnt that humans often carry food and will offer it up, even if it requires some thievery, harassment, or intimidation.

This leads to another facet of the issue, which is why these monkeys have turned so daring in the first place. It still boils down to people who deliberately feed the monkeys, despite the many warnings of heavy penalties. While habituation can create great opportunities to observe and photograph wildlife, in this case we all know too well how it generates conflict and the risk of injury to humans, and the resultant killing of macaques.

Another point to note is that despite the abundance of garbage bins, a great deal of littering still occurs in our parks. A lot of this trash consists of food wrappers and packaging, which only leads inquisitive and opportunistic monkeys to discover that human food is tasty and should be sought out, resulting in raids on bins and approaching people for handouts.

Culling is overly simplistic, and will not work in the long term, unless all the monkeys are systematically wiped out from the forests. Instead, the issue has to be tackled on several fronts. For instance, greater enforcement is needed in clamping down on people who insist on feeding monkeys. Make it easier for visitors to report feeders to park staff, with the promise of immediate action to apprehend the culprits, or for feeders to be prosecuted based on vehicle license plate numbers, since many feeders simply drive past and toss food out the window to the waiting monkeys. Improvement of bin designs to prevent monkeys from accessing their contents and to prevent tampering and vandalism by people is another avenue. Such bins should be incorporated not just within the parks, but also on the periphery, such as along streets and at bus stops.

At the same time, development of some patches of greenery could displace resident troops of macaques, causing them to venture into places where they come into closer contact with humans. Hence stronger legislative protection for some of these places and erection of buffer zones around core nature areas may be needed, in conjunction with a network of wildlife corridors for monkeys and other wildlife to safely disperse to refuges elsewhere.

However, the greatest tool is education. There have been many efforts to educate and inform the general public, and I am optimistic that compared to the past, more people are now aware of the negative consequences that may arise as a result of feeding monkeys. At the same time, I feel that it is important for park visitors to adopt behaviour that will help minimise the risk of conflict.

For example, since many monkeys now associate plastic bags with food, it is important to hide or conceal all food and drinks within a proper opaque bag, to be carried at all times. When consuming food within the park, take a good look around first to make sure that there are no monkeys watching, and then finish one's food as quickly as possible. The forest is no place for a leisurely picnic.

Always keep a respectable distance between oneself and a monkey. I've seen all too often how crowds of people may gather around a monkey to take photos and approach it while talking loudly, hollering to their companions, or squealing in delight. In one of the recently reported incidents, a victim was in close proximity to a baby monkey, which most likely provoked its mother into trying to protect her young from a perceived threat. Should a monkey get up and start moving towards you, the best course of action would be to walk away slowly and calmly. Running and screaming may excite it further, and trigger a chase, even if the monkey was not originally intending to solicit food from you.

It is also advisable for park visitors to acquaint themselves with understanding basic macaque body posture and facial expressions. For instance, if the monkey is grinning and its teeth are bared, it isn't smiling, but is instead showing fear. Being able to read a monkey's emotional state can help one determine if a particular monkey should be given a wider berth.

We need to realise that the parks and forests are not solely for our enjoyment; they are the homes of a great number of species, and we need to be mindful that it is us who are encroaching on the monkeys' domain, scaring them with our crowds and loud noises, and tempting them with food. Yes, conflict will occur now and then, but we have to be pragmatic and accept that while we can manage the risks and hope for some measure of peaceful coexistence, the occasional clashes between man and monkey cannot be completely eliminated without the total eradication of either species.

Elsewhere in the world, the prevailing perception is that nature reserves and national parks are set aside for wildlife, not people, and it is people, not animals, who bear the burden of taking extra precautions to avoid dangerous encounters. Even when animals end up attacking humans, whether it involves lions mauling park rangers in Africa, tigers pouncing on tourists in India, or bears raiding food caches and attacking campers in North America, such incidents are generally accepted as tragic but sometimes unavoidable occurrences. While an animal known to pose a threat to people may be shot, it’s understood that culling the entire population to make the parks safer for humans is not an option.

Ultimately, resolving human-wildlife conflict is more about altering human behaviour and attitudes than it is about reducing the risk of attack by wild animals.

Ivan Kwan

(Photo by 7 Years Later...)

I understand the concern for human safety. After all, getting bitten by a macaque is no joking matter.

(Photo by headshotzx)

But what a lot of people fail to understand is that the macaques are so bold simply because they have discovered that human visitors often carry tasty food that cannot be found in the forest. Being highly intelligent and curious by nature, and given how careless many people are, it's not surprising that they would have learnt this. I'm sure this was picked up only recently, since many portions of the Southern Ridges trails were opened up only relatively recently. And of course, there is always the likelihood that some selfish and irresponsible people facilitated the learning process, without regard for the consequences. There are many sites all over Southeast Asia where hordes of macaques harass tourists for food, or where tourists are actually encouraged to feed the monkeys, and the last thing we need is to have such a farce created in Singapore.

(Photo by Leonard Koh)

(Photo by Alex aka Beserk)

Many people also have this horrible habit of littering in the parks, and it goes without saying that this is where many macaques first discover the pleasures of human food, full of calories, artificial flavours and sweeteners. Scavenging is a gateway that soon leads to outright theft.

(Photo by redeath03)

(Photo by Heidi Donat)

(Photo by Synchroni)

Not to mention that some people think that they're being kind to animals, and deliberately get too close to wildlife. I can understand the warm fuzzy feeling and thrill of bonding with another species (this is why we have pets), but it's another thing to treat a wild monkey as something that you can play with safely. Besides, like us, every macaque has an individual personality. A particular mother may be permissive (or too afraid to retaliate) and allow her baby to frolick with the humans, while another may be less tolerant and attack the moment she feels a human has gotten too close.

(Photo by Longenus)

The last time I had a letter published in the Straits Times Forum, it was about someone's fear that people could be attacked by wild boar and other animals straying out of the forest and into the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) campus. While that piece focused more on wildlife wandering into human-dominated spaces, the scope of this latest issue deals with human interactions with wildlife within our parks and nature reserves, areas which most of us would identify as the animals' homes and territories.

(Photo by parachute_1)

It certainly poses a question that isn't necessarily easy to answer: do the parks belong to people, or to the monkeys?

One might immediately reply that the monkeys and other wild animals live there, and as many would argue, they have been living in such places way before we humans arrived and cleared most of the forests, building homes and factories and shopping malls and golf courses on the land where they once roamed freely. Hence, these areas are the monkeys' domain, since unlike them, no human being spends his or her entire life in the forest.

(Photo by Alex aka Beserk)

On the flipside, one may also argue that these parks were set aside by humans in the first place, and that the desires of humans must by default take precedence over the needs of all other inhabitants of the forest. If the monkeys want to continue to live there, they'd jolly well behave according to our rules, or face the consequences.

(Photo by vlazygirl)

Which then leads to the next question: Are these parks set aside for people, or for monkeys? Whose space is it? Do the forests belong to the monkeys, with us being mere trespassers and visitors? Or are these parks for the sole benefit of humans, and the monkeys ought to behave themselves, or be relegated to the truly wild corners free of human traffic?

(Photo by AskMeLah.com)

One fact about nature conservation in Singapore is that more often than not, in order for a green space to be preserved and spared from being paved over with concrete or asphalt, it has to earn a right to exist by being put to use by humans somehow. Most often, such a place is classified as a park, a place of leisure and recreation for people to visit, whether it's for a morning jog, to appreciate nature's splendours, or to spend time with a loved one. Terms like 'outdoor classroom', 'heritage', 'ecosystem services' are often tossed about, but these are still overwhelmingly anthropocentric concepts which are fixated upon how we humans can benefit from the preservation of these spaces.

Rarely do we ever talk about setting aside areas of land simply for its intrinsic ecological value, or purely for the sake of conserving biodiversity. No, in land-scarce Singapore, every parcel of land is allocated to be useful to people somehow; even unmarked patches of forest or wasteland are typically earmarked to be developed at some point in the future. And there is always the caveat that one day, should it be deemed that there is an overriding need for the land to be put to 'better' use, even our nature reserves will not be completely immune to the often unstoppable spread of cement.

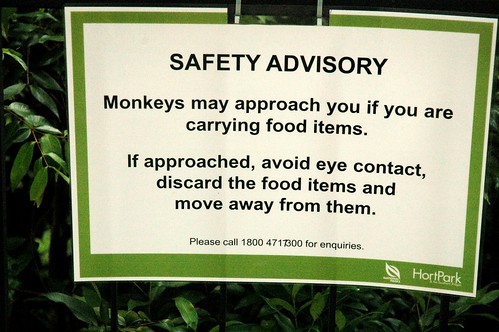

(Photo by miio2008)

Given that these parks and nature reserves are spaces created for the benefit of humans, how far should we dictate and control what goes on within these areas? After all, we already clear small areas to construct visitor centres, boardwalks, hiking trails, and shelters. We fill these spaces with boards about the park, boards with maps to guide lost visitors, boards that attempt to educate visitors about the trees and wildlife, boards that attempt to discourage visitors from poaching or carving their names on the trees, boards that remind people about the consequences of feeding the monkeys. We place rubbish bins everywhere, hoping that people would be considerate enough not to trash the very same places they have come to appreciate. Even the inhabitants are subject to our will; we deliberately plant native flora, while taking great pains to remove invasive species. Wild animals trapped in urban areas often find themselves relocated and released into unfamiliar territory in the park. Fallen trees that happen to block paths are not allowed to slowly decompose in place. The list goes on...

(Photo by andrewtansj)

Contrary to popular perception, even the forests in our nature reserves bear the marks of our desire to own and dominate nature, and to tailor it to suit our demands. Since we already control so many aspects, what's the big deal about getting rid of animals that do not adhere to the rules we impose on them? I'm sure there are plenty of people who love hiking in Bukit Timah, but who would also wish to eliminate every spider, mosquito, snake, or otherwise potentially offensive or undesirable creature.

But if we go so far as to exert so much control over these supposed wild places, then I'm not sure if we are preserving an untamed forest, or rather, a mockery of a forest, one that has to be constantly managed and manicured for our benefit. In other words, a garden.

(Photo by andrewtansj)

I believe that for most of us who visit these forests, we are there with the knowledge that nothing is predictable. The sapling you saw the last time may have since grown into a mighty tree, or the tree you noticed a few months ago might not be standing anymore. You may see a lot of wildlife, or none at all. You might get bitten by mosquitoes or stung by hornets. You may have your head split open by a falling tree. I'm sure everyone takes these risks into account, and understands that despite our best efforts, where it comes to nature, few things are ever truly entirely within our control. In fact, it is this unpredictability that often makes a visit to the forest exciting, creating positive experiences and compelling people to visit the same place repeatedly.

At the same time, we cannot deny the importance of these parks in providing critical habitat for many species, macaques included. People who argue that we should trap and relocate the monkeys to other areas where they cannot disturb human visitors don't understand one basic fact: such a place probably does not exist in any of our parks and nature reserves. Unlike neighbouring countries, where there are still large swathes of forests still relatively untouched by human activity, the monkeys are pretty much trapped in island refuges surrounded by a sea of unwelcoming urban development. Even though the long-tailed macaque is an adaptable species that still manages to tolerate some deforestation and thrive along the forest edge and in secondary vegetation, it is when they adapt to living in these peripheral zones that they are most likely to come into conflict with people. Roads that cut through forested areas, residential areas just outside the forests, and parks with high volumes of human traffic (and the inevitable supply of rubbish) become battlegrounds, with 2 primate species competing over territorial rights, a battle that the long-tailed macaques are sure to lose in the long run if intolerance and mindless adherence to temporary solutions prevail.

(Photo by raymondbPhotos)

Even within the core of Bukit Timah and Central Catchment area, where some primary rainforest still exists, it is likely that the monkeys will inevitably cross paths with parkgoers. And it's not as if the macaque troops already residing in these parts will welcome any relocated monkeys; any area of forest, no matter how productive, can only support so many monkeys before reaching its maximum carrying capacity. Besides, monkeys can disperse over great distances. If you relocate the monkeys, and expect all of them to stay put and not wander back towards other areas, it reveals just how incredibly naive you are.

(Photo by miio2008)

Culling is a sticky issue; I can see the value of culling when it is likely that there is an adverse impact on the ecosystem as a whole, or to get rid of individual macaques seen as particularly dangerous or recalcitrant. But I'm not sure if it should constitute the main form of control. Placing a trap and euthanising those that get caught doesn't do anything to eliminate the troublemakers, which are probably seasoned and too wily to be caught in this manner. Instead, it is the young, the inexperienced and the gullible that get trapped and removed.

(Photo by andrewtansj)

Suggestions that we round up all the monkeys and send them to the zoo are frankly absurd; the Singapore Zoo, for all its expertise, does not have the space and resources to care for such a large number of primates. And even if it did, there is the issue of wiping out an entire population of primates and keeping them in captivity simply to stop inconvenience to people, and the unknown ecological ramifications. I'm not sure if the word 'imprisonment' would be appropriate to use in such a scenario, but it definitely strikes me as excessive and wholly unnecessary; one might question whether the macaques, which are merely trying to survive and adapt to our presence, deserve such drastic action. It's not a matter of whether it can be done (I'm sure it's possible, if we committed an unbelievable amount of resources towards trapping every single wild monkey in Singapore), but whether it should be done.

(Photo by Laipi Photograph)

Relocating the monkeys to an offshore island, which will serve as a sanctuary is a possible second chance for those that have been trapped and would otherwise be euthanised. One such idea was proposed for Pulau Tekukor but eventually rejected. But there is the problem of encouraging a disparate band of frightened and traumatised monkeys to socialise and establish a new troop. And even if the island is large enough to provide for all their needs, the time will come when the environment cannot sustain any more monkeys, regardless of whether they are released or born there.

(Photo by Dadida)

(Photo by 7 Years Later...)

Even though the parks are undeniably created more for the benefit of humans, the fact is that they play a vital role in ensuring the continued survival of numerous other species. One can argue that the parks are even more important to wildlife than they are to people; after all, we're not the ones who spend almost our entire lives in the forest. Should we even go so far as to consider the monkeys and other wildlife to be stakeholders (albeit voiceless ones) in this struggle to coexist within these spaces? Insinuating that potentially aggressive and thieving monkeys 'don't belong' in our neighbourhoods and parks shows an extremely blinkered mindset, one that seems incapable of accepting that we are capable of living with other species in Singapore, and at the same time, insults humans' ability to innovate and come up with compromises and solutions to help resolve the issues.

(Photo by spiderman (Frank))

It doesn't have to be humans versus macaques. We can share the forests and parks. And yes, there will always be conflicts, but they can be greatly reduced and kept to a minimum if we used a lot more common sense. People who paint it as an us versus them scenario are creating unnecessary dichotomies that ignore the fact that it is possible to live together, provided we eradicated many of the problems that are created by humans in the first place.

(Photo by Alex aka Beserk)

It's this unwarranted fear, intolerance and refusal to compromise and coexist that plagues attitudes towards animals throughout Singapore. It's not just long-tailed macaques, but also snakes and monitor lizards, and common palm civets in Siglap. I still get very angry whenever I recall the resident in the Swiss Club area who apparently trapped and drowned squirrels for daring to chew his wires and leave nutshells in his garden. Even domestic animals are not exempt from paranoia and hatred; it is often an uphill battle for those involved in animal welfare, what with stray dogs being targeted for culling because of complaints (even if these dogs are usually just curious or even friendly, or simply minding their own business), and the widespread myth that cats sleeping on cars will scratch the paintwork.

(Photo by spiderman (Frank))

While searching for articles about human-wildlife conflict in parks and nature reserves elsewhere, I came upon several examples of genuinely dangerous encounters between people and the local wildlife. For instance, in 2008, a lioness with cubs mauled a ranger in South Africa's Kruger National Park. Earlier this year, 8 tourists in India's Kaziranga National Park had a narrow escape when a tigress and her 2 cubs pounced on the elephants they were riding. And last year, a man was killed and 2 other campers were injured by a grizzly bear in a campground near Yellowstone National Park..

In many North American parks, bears are a very real risk to human safety; being omnivores, they too are attracted to the food we bring into the parks and forests, requiring campers to take extra precautions in preventing bears from raiding food caches or ripping apart tents and sleeping bags (along with the people inside). While some attacks may have occurred because the bears felt startled or threatened by humans, or had become habituated to people, a number of other incidents are more likely to have been the result of a bear simply being curious and deciding to see if humans could be eaten. In August, a polar bear killed a 17 year old boy and injured 4 other tourists in Svalbard. Wolves, spotted hyenas, leopards, cougars, crocodiles and alligators too have had their fair share of dangerous encounters with people on their turf.

And that's just the predators. What about attacks by herbivores like elephants, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, and bison? Even innocuous-looking deer and kangaroos have the potential to cause serious injuries should a human end up getting attacked.

And what do we make of this incident, in which a red hartebeest collided with a cyclist?

When you look at it this way, getting scratched or chased by a macaque pales in comparison.

(Photo by miio2008)

Yet even when such unfortunate incidents occur, it is generally accepted that these are typically isolated events. Often, the animal attacked because of some action on the part of people, whether it involved someone unknowingly venturing too close, or habituated wildlife approaching humans because they are used to seeing us as a source of food. Yes, the individual responsible may end up getting killed to protect other visitors, but the idea of culling the entire population just because one of them injured or killed a person is never raised as a viable solution.

It saddens me that there are so many people who ultimately seem completely ignorant and oblivious to the fact that a lot of the blame lies with humans, or who somehow cannot find it within them to accept and tolerate the presence of other species in human-dominated spaces. The monkeys are not attacking because they are vicious wild beasts; they are simply doing what comes naturally to them in their bid to adapt and survive in such an environment. And while it will be difficult to train them not to approach people for food, or not to wander beyond park boundaries and into residential areas, it is far easier (and far more effective) to educate people to behave appropriately.

(Photo by XXVIII)

It turns out that only a small proportion of people want the macaques to be completely eliminated; in a recent study, less than 15% of respondents in a survey supported removal or eradication of macaques, with an overwhelming majority feeling that it was important to conserve and protect macaques in Singapore. Indeed, as the abstract indicates, "people living in Singapore value macaques, do not wish them entirely removed, prefer education-based solutions, and consider conservation and protection of them important."

(Photo by Alex aka Beserk)

As N. Sivasothi put it so eloquently during the recent Biodiversity of Singapore Symposium 3, we cannot let the minority who want animals eradicated hijack policy decisions or how we are managing animals. I refuse to simply keep quiet and let such paranoia, ignorance, and arrogance dictate conservation and animal welfare policies. Whenever possible, I will speak up, even if it is more for the sake of pointing out the stupidity in someone's statements, and hopefully educate others at the same time.

I'd like to digress a little with a comic strip from the brilliant XKCD, one that so perfectly encapsulates why I channel my energy towards correcting misconceptions and ignorance, and doing my bit to help educate and raise awareness of certain issues. It explains why I risk permanent brain damage by checking STOMP on a regular basis, and spend the time writing letters to the press that aren't always published.

The term 'keyboard warrior' often carries negative connotations, describing people who are often full of hot air online, but who don't lift a finger to solve issues in the real world. But what I've realised is that a lot of communication and outreach takes place in online spheres. Whether it's via Twitter, Facebook, Google+, YouTube, or somewhat more traditional platforms such as blogs and forums, there is a lot of potential to reach out to people who might not otherwise learn how our actions can have a great impact on the natural world. It's so easy to share content and ideas these days, and while I often end up rolling my eyes or doing a facepalm at blatant showcases of idiocy, it also means that this is a very important avenue for correct misconceptions and helping people to learn something. As long as we can reach out beyond the regrettably small circles of like-minded people, and enable our peers to gain new insights and perspectives, then it would have been worth it.

We often lament how the Singapore education system overlooks ecological literacy; even students in the life sciences are often woefully ignorant of local biodiversity. But perhaps, we should see this instead as a challenge for us to bridge the gaps and to correct this deficiency in our own way. If schools and teachers are not doing enough to inculcate an appreciation for the ecological relationships that sustain the vast diversity of life in all its glorious and bizarre splendour, and the importance of sustainability and ensuring that we don't trash our only home too badly, then perhaps it is up to concerned citizens like us to step in and make sure that at least some children gain some level of understanding and concern for the environment.

(Photo by miio2008)

Many of us dream of becoming full-time nature guides, animal welfare activists, or park rangers. Others may aspire to work in zoos, aquariums, and other institutions that often provide a vital role in captive breeding and outreach. And some of us may harbour a secret desire to delve into wildlife photography and documentary filmmaking. Not all of us will be able to achieve these dreams. But I'm sure a great number of us are able to wield a keyboard with some level of proficiency, and know how it can be used as a tool to inform and educate, with the occasional online smackdown as a bonus.

I am a wildlife keyboard warrior, and I'm proud to be one.