STOMPer Swimmer caught sight of these flower crabs washed ashore the Jalan Selimang beach and shares this with STOMPers. He says:

"These pictures were taken at the beach between Jalan Selimang and the Straits of Johor.

"The beach is sandy and during high tide this place is ideal for swimming and fishing.

"On Sundays the place is crowded with picnickers and foreign workers.

"This angler was enjoying himself by fishing near the sea.

"At low tide I could see lots of flower crabs (Portunus pelagicus) being washed ashore.

"These are aquatic crabs and cannot live long outside water. They are caught with traps and nets.

"Flower crabs are carnivores, coming in with the tide to hunt fish and other animals living in the sand.

"The blood cockle (Anadara granosa) is a bivalve found at the area where the river discharges into the sea.

"The red pigment in the cockle is haemoglobin, similar to that in human blood. The haemoglobin in the cockle assists in transporting oxygen within the body and may help the clams live in the oxygen-poor habitats.

"It is usually added raw to our favourite 'char kuay teow'.

"The common name for this bivalve is 'see hum'.

"The shell surface is ribbed with small, rounded beads on the ribs."

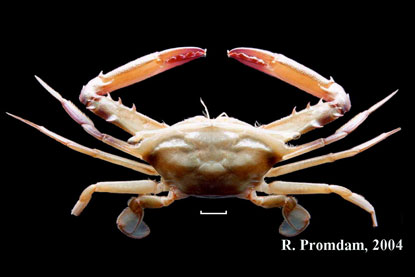

Flower crabs (Portunus pelagicus) are very commonly encountered on most of Singapore's shores, especially in sandy or muddy areas, or with seagrasses and seaweeds.

Recent research has revealed that what was traditionally thought to be a single species called the flower crab is actually a species complex with 4 separate species. Besides Portunus pelagicus, the other 3 species are P. armatus, P. reticulatus and P. segnis. Hopefully, more details will be published soon. A similar situation has occurred for the mud crabs (Scylla spp.), which were previously all considered to belong to a single species.

Both the flower crabs and mud crabs belong to the family known as the swimming crabs (F. Portunidae). This family is very distinctive, as the last pair of legs is modified into paddles, enabling the crab to swim at great speed when threatened.

Swimming crabs can be quite aggressive, and will often turn to face a potential threat with pincers outstretched, ready to give a painful nip if necessary. On more than one occasion, I've learned that my gloves are quite useless against swimming crab pincers.

These crabs are active predators, and will feed on a wide range of prey. The mud crabs seem to be fond of molluscs such as snails and bivalves; the shells are no match against the crushing force exerted by the pincers. Other species are capable of catching fish.

Chocolate swimming crab (Thalamita spinimana) with halfbeak (F. Hemiramphidae) prey, Pulau Hantu;

(Photo by Ria)

Many species of swimming crab have been recorded to occur in Singapore, and the following are some of the species which have been encountered on our shore trips.

Flower crab (Portunus pelagicus), Cyrene Reef;

(Photo by Marcus)

The most widespread and common species is probably the flower crab.

Purple mud crab (Scylla tranquebarica), Pulau Semakau;

(Photo by Marcus)

The mud crabs are rarely if ever encountered on our shore trips. However, it is likely that every Singaporean has seen mud crabs before, given how much we love chilli crab and black pepper crab.

Chilli crab;

(Photo by Silver Surfer2005)

There was a great deal of taxonomic confusion in the past, and a single species was recognised, the giant mud crab (Scylla serrata). However, further research has shown genetic and anatomical differences, indicating that there are actually 4 distinct species, and that little if any hybridisation occurs between the species.

The purple mud crab is often found in mangroves with reduced salinity, which is also the preferred habitat of the orange mud crab (Scylla olivacea). Another species, the green mud crab (Scylla paramamosain), is associated with coral rubble and sandier areas in Singapore. So far, the only species that has been encountered on our shore trips is the purple mud crab, in places such as Pasir Ris, Pulau Semakau and Chek Jawa. I once spotted an orange mud crab in the mangroves of Pasir Ris, and for several months last year, another orange mud crab used to lurk in a burrow close to the boardwalk at Chek Jawa. So far, I don't think any of us has spotted the green mud crab in the wild yet.

Giant mud crab? (Scylla serrata), Changi;

(Photo by Ria)

This photo is quite intriguing however, as based on the coloration, the closest match I can think of is the giant mud crab. If this is indeed a giant mud crab, it would be a notable discovery, as I believe that no conclusive records of this species exist for our waters. Even if giant mud crabs have been recorded in Singapore, it is possible that these were of captive origin; some Buddhist devotees are known to purchase mud crabs for release into the wild, in a misguided attempt to gain karma.

Compared to its relatives, the giant mud crab prefers mangroves with a stronger marine influence, which are regularly inundated by full-strength seawater. This is the largest species of mud crab, and is commonly known as the 'Sri Lanka crab'.

Other species of swimming crab found in Singapore are not as heavily exploited for seafood as the flower crab and mud crabs.

Three-spot swimming crab (Portunus sanguinolentus), Thailand;

(Photo by Crab Hunter)

The three-spot swimming crab is a major seafood species elsewhere, although I've yet to see it for sale in Singapore. This is a species that we haven't encountered on our shore trips. There is however a preserved specimen in the public gallery of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research.

Sentinel swimming crab (Podophthalmus vigil), Thailand;

(Photo by Crab Hunter)

Similarly, none of us have encountered the sentinel swimming crab on our shores, but there's a specimen in the RMBR public gallery, and it's also been featured in books on our marine life, such as Rhythm of the Sea: The Life and Times of Labrador Beach and Private Lives: an exposé of Singapore's shores.

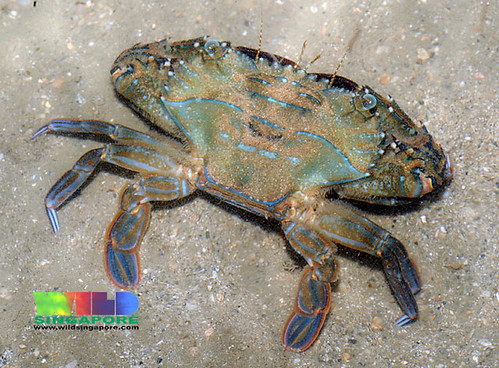

Among the more common swimming crabs are various species belonging to the genus Thalamita. These seem to prefer rocky areas, reefs and coral rubble.

Notched swimming crab? (Thalamita crenata), Tanah Merah;

Blue swimming crab (Thalamita ?danae), Kusu Island;

(Photo by Ria)

Blue-spined swimming crab (Thalamita ?prymna), Sentosa;

(Photo by Ria)

Red swimming crab (Thalamita spinimana), Sisters' Islands;

(Photo by Ria)

Chocolate swimming crab, Pulau Sekudu;

(Photo by Ria)

The so-called chocolate swimming crab is possibly the same species as the red swimming crab.

The taxonomy of our Thalamita crabs is a little unclear; Nonn Panitvong aka Crab Hunter has offered his expert opinion as to the identity of our swimming crabs. For now, these are still tentative, and I hope that we'll receive further confirmation in the near future.

Another important genus is Charybdis, which are seen less often on our shores compared to Portunus and Thalamita.

Purple-legged swimming crab (Charybdis hellerii), Chek Jawa;

(Photo by Ria)

Banded-leg swimming crab (Charybdis annulata), Labrador;

(Photo by Ria)

Crucifix crab (Charybdis feriata), Thailand;

(Photo by Crab Hunter)

The crucifix crab is another species that is heavily utilised for seafood in the region. It was spotted once at Chek Jawa in 2005.

I find it interesting that some of the genus names given to the swimming crabs are based on ancient Greek or Roman mythology. In Greek mythology, Scylla and Charybdis are infamous sea monsters, while Portunus is a Roman god.

Gazami crab (Portunus trituberculatus);

(Picture from Wikipedia)

A close relative of the flower crab, the gazami crab is the most widely fished species of crab in the world, and is especially important in Japanese cuisine. Given its wide distribution in the Indo-Pacific, it is likely that this species exists in Singapore's waters. I won't be surprised if we have actually encountered gazami crabs before, but assumed that they were just flower crabs.

Blue crab (Callinectes sapidus), Louisiana;

(Photo by jere7my)

North Americans will be very familiar with the blue crab, a native of the western Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

Like the flower crabs and mud crabs, the blood cockle (Anadara granosa) is a very important seafood species in the region. Although much reduced in number, large populations of this bivalve can be found in some of the silty and slightly muddy shores along the northern parts of Singapore.

Blood cockle (also known locally as "see ham"), Vietnam;

(Photo by stefan77dd)

The blood cockle's body is reddish as it contains haemoglobin, the very same iron-based compound that makes our blood red. The haemoglobin assists in transportation of oxygen in the body, and apparently help the cockle survive in anoxic environments.

The blood cockle supports the largest molluscan fishery in Malaysia, with an annual catch of more than 75,000 metric tonnes. Here in Singapore, it is most commonly seen as an ingredient in char kuay teow and laksa, or boiled and eaten on its own with a dash of chilli sauce.

Boiled blood cockles, Lau Pa Sat;

(Photo by ex0rzist)

Left: Anadara nodifera, Straits of Malacca;

Right: Anadara antiquata, Bintan;

(Photos from seashellhub)

There are actually several species of blood cockle known from Singapore. There is a larger species known as Anadara nodifera that is sometimes sold alongside A. granosa; this species appears to prefer sandier habitats than A. granosa. A. antiquata is suspected to occur locally, as empty shells belonging to this species have been found washed up on some of our shores.

Anadara inaequivalvis, Thailand;

(Photo from seashellhub)

Another species, A. inaequivalvis, is sufficiently different that it is given the subgenus Scapharca, which in turn is sometimes considered to be an entirely separate genus from Anadara. Several related species from the seas around Japan are known as akagai (赤貝), and feature prominently in sushi and sashimi.

The blood cockles belong to the family known as ark shells (F. Arcidae). As confusing as it sounds, blood cockles are only distantly related to the true cockles, which form a separate family (F. Cardiidae).

Among the true cockle species that can be found in Singapore include several species of large cockle (Trachycardium spp.). Despite looking similar to the blood cockles in external appearance, these large cockles lack haemoglobin in their tissues. In Japan, they are known as torigai (鳥貝).

Left: Trachycardium asiaticum, Singapore;

Right: Trachycardium flavum, Bintan;

(Photos from seashellhub)

Another species of cockle that we find occasionally on our shores is the heart cockle (Corculum cardissa).

Heart cockle, Pulau Semakau;

(Photo by Ria)

Hopefully, the population of flower crabs and blood cockles along this stretch of shore is large and stable enough to support some level of collection; it would certainly be tragic to have yet another area decimated by thoughtless people who fail to understand the concept of sustainable seafood.