STOMPer Wen Bin was on a photo taking outing with a friend when he changed upon people whom he thinks are Botanic Gardens staff manhandling a fish.

In an email to STOMP today (Mar 6), the STOMPer wrote:

"I went to the Singapore Botanic Gardens for a photo taking outing with my friend. We were walking halfway when we chanced upon some staff believed to be from Botanic Gardens manhandling a fish.

"This was about 5:43pm yesterday (Mar 5).

"We absolutely had no idea where did the fish came from.

"The man in the red polo was actually holding a tool and trying to pry into the dying fish's mouth. The fish was still struggling and after some time it became motionless.

"I do not know what tool was the guy holding and its specific purpose.. But I can see clearly that he was trying to pry into the fish's mouth with the tool.

"After the mishandling, the red polo guy just used the tool and lifted up the fish from its mouth, and transferred it into a container and moved off in a bungy car.

"I am eager to find out what actually happened and why was the fish handled in such a cruel way?

"Perhaps they could have done it in a less open space and away from the public?"

Update: Fish manhandled? Botanic Gardens: It was transferred from overpopulated area (7th March 2009)

Well, if you were so curious to find out what they were doing, why didn't you ask them?

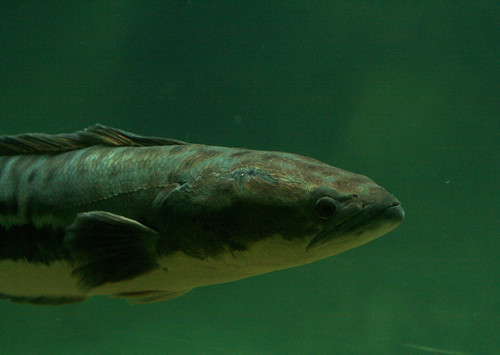

I'm quite sure that the fish in the photo is a giant snakehead (Channa micropeltes), also known as toman. While the giant snakehead is found in large rivers and lakes throughout Southeast Asia, from Thailand and Indochina to Sumatra and Borneo, it is believed that this species is not native to Singapore. Its presence in our waters is likely to be a result of the giant snakehead being commonly raised throughout the region for food and sport, with escapees and deliberate releases leading to the establishment of giant snakehead populations in our reservoirs and ponds.

Giant snakehead

(Photo from Fishing Adventures Thailand)

Freshwater Fishes of Southeast Asia: Giant Snakehead

The giant snakehead is one of the world's largest species of snakehead, reaching around a metre in length. Only the bullseye snakehead (Channa marulius) of the Indian subcontinent and Indochina is larger; it is said to reach around 120 centimetres in length. Very large individuals of the northern snakehead (Channa argus) and common snakehead (Channa striata) can reach close to 90 centimetres in length. Of course, there are reports of these snakehead species reaching much larger sizes, although such accounts are difficult to verify. The rest of the snakeheads are more modestly sized, with most of them ranging from 15 to 40 centimetres in length.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

The four largest species of snakehead.

Upper left: Giant snakehead; Upper right: Bullseye snakehead;

Lower left: Northern snakehead; Lower right: Common snakehead;

Regardless of their size, all snakeheads are voracious ambush predators that will readily eat any animal that will fit into their mouths, which are filled with razor-sharp teeth.

And this is why you don't stick your fingers into a snakehead's mouth.

Seriously, don't do it, unless you want your hand to end up like this tilapia (Oreochromis sp.).

As adults, much of their diet consists of smaller fish, and they are not above cannibalism. Frogs are also fair game; anglers all over Asia seem to swear by the effectiveness of live frogs as bait for snakeheads. Even rats and aquatic birds are not safe. Essentially, they are the tropical equivalent of the pikes (F. Esocidae) found in temperate North America and Eurasia.

Various species of snakeheads are commercially valuable, as they are prized for their flesh; locally, it is said that snakehead meat has medicinal value and healing properties, and is recommended for people with illnesses or recovering after surgery. Many species are raised in aquaculture, such as the giant snakehead, bullseye snakehead, northern snakehead, common snakehead, Chinese snakehead (Channa asiatica), blotched snakehead (Channa maculata), spotted snakehead (Channa punctata) and African snakehead (Parachanna obscura).

Four species of snakehead raised in aquaculture for food.

Upper left: Chinese snakehead; Upper right: Blotched snakehead;

Lower left: Spotted snakehead; Lower right: African snakehead;

Snakeheads are also highly popular with anglers, as they are very strong fighters when hooked. Just as how North America has its largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and Australia has its barramundi (Lates calcarifer), so the giant snakehead is an iconic species for the sport fishing industry in Southeast Asia.

Fishing for giant snakehead in Tasik Air Ganda, Perak, Malaysia.

(Photos by mohd fahmi)

The 33 or so species of snakeheads form the family Channidae, with new species still being described. 3 members of the genus Parachanna are native to Central and West Africa, while the rest of the species belong to the genus Channa and are found in tropical and temperate rivers, lakes and swamps of the Indian subcontinent and South-east and East Asia. They are capable of breathing atmospheric air, with the help of a primitive labyrinth organ similar to that found in the anabantoids which I blogged about previously; in fact, it is believed that snakeheads are closely related to the anabantoids. One can certainly see the similarities between a snakehead and the climbing perch (Anabas testudineus). Also, like many anabantoids, various snakeheads are capable of surviving for a long time out of water, and some species are also able to travel for some distance over land.

This giant snakehead had leaped out of its concrete tank at Khai Seng Trading & Fish Farm, and was swiftly wriggling across the ground. Unfortunately, it stopped moving when I tried to take a video. It was eventually found and retrieved by a passing farm worker.

Because of their durability and ability to survive out of water (a trait that is found in many Asian fish species commonly reared for food), one often finds live snakeheads being sold in markets in pails and baskets, often without water; they are able to survive as long as their skins are kept moist.

Left: Live giant snakehead in Phnom Penh market (Photo by phil.lees);

Right: Live blotched snakehead in Hanoi market (Photo by neener_7);

Due to their popularity as food fish, snakeheads have been introduced to several parts of the world.

The northern snakehead has been introduced to the rivers of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Japan, which has no native snakeheads, is now home to both northern snakehead and blotched snakehead. Similarly, Taiwan has no native snakeheads, but now has the Chinese and blotched snakeheads. Blotched snakehead as well as common snakehead are now found in the Philippines, an archipelago which did not have any native snakeheads. Common snakehead are now widely distributed all over Indonesia due to human introductions. Outside of Asia, the blotched snakehead is now recorded in waters of Madasgascar and the island of Oahu on Hawaii. Several species of snakeheads have been recorded to occur in the United States of America, and have caused much concern on the possible ecological impact, but more on that later.

Reproductive behaviour remains unknown for some species, but many snakehead species build circular nests out of aquatic vegetation, while others are mouthbrooders. After the eggs hatch, one or both parents may continue to guard the fry for some time. The parents are so protective that giant snakeheads are known to attack and injure people that approach the fry! In fact, one proven method of catching snakeheads is to look out for a breeding pair guarding a brood of young fry. The fry will rise to the surface for air, creating lots of tiny ripples, while the parents will be cruising nearby. Casting a lure into the school of baby snakeheads will trigger a defensive response from one of the parents, which will attempt to drive away the intruder, only to be hooked and reeled in.

Pair of giant snakehead guarding brood, MacRitchie Reservoir

(Photo taken from Ecology Asia)

There is also some demand for snakeheads in the aquarium trade; the smaller species are often attractively coloured, while the larger species make majestic and imposing subjects for zoos and public aquaria. As a whole, the family is relatively undemanding, and snakeheads in general are not fussy where it comes to water conditions.

4 snakehead species found in the aquarium trade.

Upper left: Orange-spotted snakehead (Channa aurantimaculata);

Upper right: Ocellated snakehead(Channa pleurophthalma);

Lower left: Rainbow snakehead (Channa bleheri);

Lower right: Golden snakehead (Channa stewartii);

Giant snakehead in Singapore Zoo

(Photo by pederseni)

Snakeheads are not picky eaters, although it can be difficult or even impossible to wean wild-caught individuals off live fish. Due to their prodigious appetites, and the fact that most will refuse to touch commercially prepared fish food such as flakes or pellets, they can be quite expensive to feed. Being messy feeders, an aquarium for a snakehead requires excellent filtration.

It is essential to choose tankmates wisely; any smaller fish will eventually be food for the snakehead. Even fish too large for the snakehead to swallow whole may get ripped to shreds, or have chunks bitten off. Snakeheads are territorial, so keeping more than one snakehead in the same aquarium is usually out of the question. Some of the larger species, like the giant and northern snakeheads, are gregarious to some degree, and will form small schools in the wild. Needless to say, an aquarium for a group of adult giant snakeheads will have to be very large.

Being ambush predators, snakeheads are most comfortable in aquariums with adequate hiding places, a task that becomes quite a challenge when one is dealing with a metre-long monster. Plants, rocks and driftwood will all help to make the snakehead feel at home, although such decorations must be well-anchored to prevent the fish from toppling them over. Like anabantoids, it is vital to ensure that the snakehead is able to reach the surface to breathe air, otherwise it might drown. One final essential piece of equipment for any aquarist planning to keep a snakehead is a sturdy cover for the aquarium; snakeheads can be skittish and are very capable jumpers.

It is important to provide adequate space, especially for the larger species. If spooked, a snakehead might just swim right into the glass and seriously injure itself, and maybe even crack the glass.

This video clip I took at Khai Seng Trading & Fish Farm demonstrates how skittish even large snakeheads can be:

Snakeheads spooking from Ivan Kwan on Vimeo.

For obvious reasons, the larger snakehead species are really not suitable for the home aquarium. Yet, it is not uncommon to find baby giant snakehead being sold in pet shops. When young, they are attractively coloured and form small schools. Due to its appearance at this age, the giant snakehead is commonly known in the trade as the red snakehead.

(Photo by thelousycaster)

Unsuspecting individuals who purchase a snakehead on impulse soon discover what they are in for. Adding a baby snakehead to a community aquarium is only asking for trouble. Before long, there is only one fish left in the aquarium - a very fat and satisfied snakehead. If purchased as a group, the baby snakeheads all seem to get along with each other. However, they soon become more intolerant of each other's company, and any smaller or weaker individuals are quickly set upon and devoured. Once again, this behaviour often continues until there is a sole survivor, having either eaten or savaged the rest of its siblings.

A baby snakehead soon outgrows its living quarters, and demands more space and food. Not only that, but the attractive coloration quickly fades away. Combine this with a mean and aggressive disposition, and a willingness to bite the hand that feeds it, and it is not surprising that many people end up regretting making the decision to purchase that cute baby giant snakehead.

From an attractively patterned 20-centimetre juvenile...

...To a metre-long monster.

It is unfortunate that this practice of selling baby giant snakeheads is still widespread, and that people don't do their homework before making that impulse buy. I wonder how many community aquariums have been decimated by the addition of a baby snakehead, or how many adult snakeheads end up languishing in fish tanks far too small for them. This problem is prevalent in the aquarium trade, with far too many species being sold without customers being aware of the fact that the cute little fish will quickly eat all its tankmates, and soon grow into a huge ugly monster that will not hesitate to snack on your fingers. At the same time, many people are ill-prepared for the level of commitment and responsibility that comes with keeping such massive fish in an aquarium; not all zoos and public aquaria will be willing to take in unwanted fish.

Several species of snakeheads have been reported in waters outside of their native range, and while most of these were a result of snakeheads escaping from the live food fish trade, deliberate releases by well-meaning individuals and irresponsible aquarists are responsible for some of these reports.

There is much fear about snakeheads becoming established in North American waters, due to the possible adverse impacts on other fish species. Because these fish are traditionally sold alive, and because of the ever-present possibility of unwanted aquarium fish being discarded, there is some risk that certain snakehead species will end up in American lakes and rivers. The species of greatest concern is the northern snakehead; its native range encompasses parts of China, Russia and the Korean Peninsula, and is tolerant of cold temperatures. It is potentially able to survive over a large area of North America, unlike other species of snakehead, which would be restricted to the warmer states.

Invasion of the Snakeheads

A northern snakehead was collected in a California reservoir in 1997, but did not cause any alarm. Several individuals of the same species were recorded in Florida in 2000, as was a single specimen from Massachusetts in 2001. This species is not common in aquaria, but is an important food fish, so it is likely that these individuals originated from the food fish trade, or might have even been deliberately released thanks to the common Buddhist practice of releasing animals to gain merit. Indeed, as we shall see, it is possible that such behaviour can be implicated in many reports of snakeheads in the United States.

A breeding population of bullseye snakehead was discovered in Florida in 2000. This species is known in both the food fish and aquarium trade, so abandonment by aquarists cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that it was illegally released by irresponsible anglers seeking to experience the thrill of hunting this species without having to travel to Asia.

It was the discovery of northern snakehead in Crofton Pond, Maryland in 2002 that triggered a wave of hysteria over the presence of snakehead in American waters. It all started when a single adult was caught by anglers, who were unable to identify it. Then, a second adult was captured, along with several babies. That same year, in an unrelated incident, 2 northern snakehead were caught in Lake Wylie, a reservoir in North Carolina. All Hell broke loose, with exaggerated news reports fanning the fear about snakeheads, now dubbed 'Frankenfish', crawling overland to decimate lakes and rivers all over the country.

When the pond was treated with the poison rotenone to kill all of its fish, more than a thousand baby snakeheads were recovered from the pond. The origin of the Crofton Pond snakeheads was soon discovered:

Around 2000, a man who lived in Crofton had ordered two live snakeheads from an Asian fish market in New York, wanting to make his sister, who was ill, a pot of snakehead soup. But the sister got better before the fish hit the pot. The snakeheads, a male and a female, were set free in the pond. They made babies.

Not only did the incident illustrate the threat of invasive species, it also resulted in the release of 2 awful B-grade movies in 2004, Frankenfish and Snakehead Terror.

Subsequently, a population of northern snakehead was discovered in 2004, inhabiting a section of the Potomac River. What was more worrying, was that both adults and immature individuals were found, indicating that this population was breeding. Poisoning a pond to get rid of all the snakeheads is one thing, but eradicating snakeheads from a major river like the Potomac is another. They have now become an established component of the Potomac's fish fauna. Genetic studies have revealed that the Potomac snakeheads are not closely related to those from Crofton Pond, allaying fears that the snakeheads had spread from Crofton. Instead, the Potomac snakeheads are the result of one or more separate introductions.

The Northern Snakehead Channa argus (Anabantomorpha: Channidae), a non-indigenous fish species in the Potomac River, U.S.A.

Tracking the Spread of Northern Snakehead Fish

Some of the Frankenfish hype has turned out to be overblown; the northern snakehead has limited ability to travel overland, and they have not wiped out other fish species in the river.

Scientists Challenge Snakehead Myths

Snakehead: Fish Out of Water

While the distribution of the species in the Potomac is restricted by the Great Falls upstream, and the saline waters of Chesapeake Bay downstream, there are fears that it might negatively affect the populations of commercially valuable species such as the American shad (Alosa sapidissima) and largemouth bass (which is also not native to the Potomac). At the same time, there is some potential for developing a small sport fishing industry around the northern snakehead, which would help to control their numbers.

Potomac Fever

Also in 2004, a second northern snakehead was found in Massachusetts, while one was caught in Lake Michigan. That year, another breeding population of northern snakehead was discovered in a pond in Pennsylvania, and is believed to have spread to the Delaware River by now.

Such incidents led several states to impose a ban on all species of snakehead, making it illegal to possess, sell, and transport live snakeheads. It's a law that many aquarists have found to be excessively harsh and unfair, especially since most snakehead species are tropical, and would be unable to survive winter in most states. While many snakeheads were seized from pet owners and fish markets and destroyed, it is possible that some individuals released their pets to avoid being caught. And despite the existence of such laws, various investigative reports have shown that it is still possible to purchase live snakeheads from some fish markets, while trade in pet snakeheads still occurs between individuals over the Internet.

Fish or Foul? What you don't know about DC's notorious snakehead fish... and the people who love them.

In 2005, 4 northern snakehead were collected from a lake in New York City. In 2007, another northern snakehead was caught in Lake Wylie, North Carolina. And in 2008, yet another breeding population of northern snakehead was found around Caitlin Creek and Ridgebury Lake in New York.

Northern snakeheads popped up in yet another state in 2008, when they were found to be breeding in a drainage ditch in Arkansas. Apparently, in 2000, a shipment of northern snakehead was sent to a fish farmer there, who was advised to get rid of his stock as discussions were then in place to list the northern snakehead as an injurious species. The farmer disposed of the snakeheads by netting them and dumping them onto a levee. No doubt, some of them must have survived long enough to make their way to the nearby ditch, where they started breeding. Heavy rains might have already washed some of the snakeheads into other parts of the drainage basin, where there is a chance that they will eventually spread into the St. Francis, Arkansas and Mississippi rivers.

While the northern snakehead has been the species most commonly encountered in such incidents, other species have also been involved. As seen earlier, the bullseye snakehead is known to be breeding in Florida, and there seems to be little that will prevent it from spreading its range further throughout the warmer parts of the state. 2 blotched snakehead, another species able to survive in temperate climates, were caught in a Boston river in 2001. The giant snakehead itself has been discovered on several occasions; individuals have turned up in recent years in Maryland, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Wisconsin. Being a tropical species, giant snakeheads are incapable of surviving winter in these states, and these incidents were most probably due to abandonment of unwanted pets. However, any giant snakeheads that are released in states such as Hawaii or Florida, where temperatures are warm enough for them to survive all year round, would definitely pose a real problem.

Here in Singapore, it is not known if the giant snakehead has any major ecological impact. Since it is after all native to the region, I would think that it is likely that our native fishes are able to coexist alongside it. The giant snakehead might however compete with or even prey upon the smaller native snakehead species. Apart from the giant snakehead and common snakehead (which is also known locally as aruan or haruan), our remaining snakeheads are quite rare and restricted to streams in our Central Nature Reserves. They are the dwarf snakehead (Channa gachua), forest snakehead (Channa lucius), and black snakehead (Channa melasoma).

Singapore's native snakeheads

Upper left: Dwarf snakehead; Upper right: Forest snakehead;

Lower left: Black snakehead; Lower right: Common snakehead;

The U.S. Geological Survey has compiled an excellent online resource on snakeheads.

Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae) - A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment

Returning to the original post, I have no idea what the people were doing to the snakehead. Maybe somebody was caught fishing, and the snakehead was being resuscitated. It is possible that they were removing a non-native species from the lake, although to be honest, the lakes in the Singapore Botanic Gardens are already so full of introduced species that removing giant snakehead won't make much difference anyway. Perhaps the black swans (Cygnus atratus) and mute swans (Cygnus olor) that live around the lakes are breeding, and the giant snakehead is being removed to protect the cygnets. But unless the Singapore Botanic Gardens staff explain to us what is going on, the whole reason why this fish is being moved will remain a mystery.